The 1970s were a time of economic malaise for the west. Weirdly, the Soviet Union was chugging along at its own egregious and bizarre pace, and Soviet air travel needs had never been more pressing. Millions of Warsaw Pact and Soviet citizens needed to shuttle around the Iron living room. In fact, Aeroflot celebrated its hundred-millionth-passenger year in 1976. This called for larger aircraft. Engine technology issues were holding up Ilyushin’s domestic design, which we now know as the mostly-extinct IL-86.

The program to which the IL-86 stemmed from was formally known as the “aerobus”. The IL-86 was not supposed to be the only aircraft of the family of short, medium, and long-haul indigenous widebody aircraft.

Believe it or not, Tupolev almost built a similar aircraft (but widebody) to the Dassault Mercure. Photo: Alain Durand

Tupolev had stepped up to offer the Tu-184, an aircraft that was similar to a twin-aisle Dassault Mercure. Thankfully, at the time of its inception Andre Tupolev was still alive. He took one look at it and decided that the company should not waste any resources on what he was sure would be nothing but a reputation-wrecking disaster. Not that Tupolev was immune to civil aviation failures, they are simply beyond the scope of this article. They were also, usually, swept under the rug and blamed on Myashischev (a competing design bureau).

The IL-86 itself was originally supposed to be a widebody IL-62. Same T-tail, similar cabin-window layout, and identical engine positions. The Soviet government stepped in and said that the design “looked antiquated”. That was the end of that.

The next set of aerobus edicts demanded wing-mounted engines and a “modern” six-to-eight-piece flight deck window set. Would the original IL-86 studies have been more successful than what the Soviets ended up with? Probably not, as there was really nothing in their engine arsenal that had the bypass ratios to produce either the thrust or the necessary efficiency.

If that was not enough, the government, suspicious that airports in Siberia would not be able to offload baggage quickly, demanded that their precious aerobus had something eventually dubbed the “luggage at hand” system. In other words, passengers would check their own bags in after boarding through airstairs built into the lower deck. During the latter days of the IL-86, this was never used.

The original IL-86 was going to be nothing more than a widebody IL-62 – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

As the IL-86 was going nowhere, the Soviets, in a rather landmark move reached out to American manufacturers. McDonnell Douglas balked. However, Lockheed, suffering from their own engine issues and always a company interested in earning political capital, decided to send an L-1011 to Moscow in March of 1974.

In what, at the time, must have come as a surprise, the Soviets decided to order 30 L-1011s. They also wanted to build up to 100 per year domestically. It would have been a landmark order in monetary terms, and probably changed some of the dynamics of the Cold War. But we can’t have that now, can we?

President Carter had the DOD and Department of Commerce investigate any potential ITARS issues. Naturally, there was a tangential one. The RB-211 engine used composite fan-blades. The Soviets had no industrial process for that, nor did they ever consider it a wise idea (something Rolls Royce probably wished they had decided). The deal, as if by design, fell apart.

A Delta Air Lines’ L1011. Photo: Ken Fielding

If that was not enough, the Department of Commerce also blocked the sale of General Electric CF-6-50 engines. The Soviets had planned to use this engine in their own indigenous wide-body projects. The Soviet high-bypass engine solutions were running behind schedule, and the L-1011 deal would have allowed them the necessary time to properly develop an iteration of the IL-86, probably CF-6 powered. When Soviet engines of the same thrust class were ready, there would be indigenously-powered versions only.

Strangely, if the deal had gone through, the Soviet Union (then Russia and the former Republics) would actually have not only been the largest operator of the L-1011, but also would have built far more than the parent designer.

The Russians, feeling rather jilted and already in possession of measurements and actual Lockheed L-1011 documentation, decided to not let this denial get them down. Being the largest, oldest, and most politically-active OKB of the Soviet Union, Tupolev decided that they could step up.

Having said that, this design was so far from clean-sheet, Antonov, Yakovlev, TANKT Beriev, and even Myashishchev were also told to do the same. Outright design copying was actually strictly forbidden. It was a very strict code amongst Soviet engineers that they would always come up with an indigenous solution. Indeed, building too many copies of the Me-262 cost Semyon Alekseyev his design bureau, resulting in the shuttering of OKB-1, and the unfortunate creation of the Baade 152.

I say that they did not let the documentation and measurements they had go to waste because the requirement from the government was almost literally, “you will build us an L-1011. It will be this long, or longer.” Not much freedom there.

Yakovlev managed to lose all its civil credibility just as the project was gaining momentum. The series of disasters with the early Yak-42s all but sidelined them from any L-1011 cloning.

Myashischev, deciding to do what they always did, ignored the RFP and decided to draw pictures of what a five-year-old would think an airplane would look like after being fed a package of gummy bears.

By the late 1980’s, when Myashischev had run out of money, the resulting M-52 is something that lacks polite description. The project was only allowed to continue for so long as the passenger pod could be replaced with relevant, heavy, space-related payloads.

TANKT Beriev, much like Myashishchev, thought the best way to get anywhere with the project was to bring it into a realm they could understand. That realm, as for most things Beriev, was water. While I cannot directly source just how many of their 1970s to mid-80s lifting body flying boats were 100% attributable to the aerobus specifications, there were definitely 3-5-3 (500 seat) models described in the brochures as “aerobuses.”

Now that we have seen what the perennial also-rans of Soviet experimental design companies came up with, it is time to look at what the “adults” designed. I should mention that by the 1970s, at least in the case of Myashischev, when they actually designed something correctly the projects were usually stolen and put under the stewardship of a more mature OKB.

Guess what? They all look like the L-1011. So much so that I’ve started to call them Tri-Zvezdy.

The most fascinating part of this saga is that Tupolev’s L-1011-esque widebody passenger aircraft was to be called the Tu-204. Except this Tu-204 was going to sport high-bypass engines made by Lotarev, and seat between 350 and 400 people. As you can probably see, it included some fairly distinctive Tupolev passenger aircraft features.

If the engines had matched their prospective performance targets (and they did to some degree; these are the same engines that eventually became the Ivchenko-Progress D-18Ts used on the AN-124) the aircraft would have had a range similar to that of the L-1011-500. I am told that the registration on the model indicates that Tupolev believed that the latest they would get their superstar into service with Aeroflot was 1987 or 1988.

Eventually, Tupolev realized that Ilyushin had the “larger than twin” aircraft market locked down and turned the Tu-204 into more of an A330-size aircraft. Still, seen as too large, it became the aircraft we know today (which looks very similar to the Boeing 757).

Antonov, somewhat a stranger to the widebody world, took some advanced papers on wing-related induced drag – and thought the solution was to take a design almost identical to the above Tu-204 and put winglets on it. It was not a bad idea; their version would have had a longer range.

All of those were great ideas, but why were they never built? Politics. Ilyushin was always able to convince the government that whilst their current IL-86 was vastly underperforming and experiencing issues operating in cold climates, the “real” IL-86 was just around the corner. What also saved the IL-86 was that it had such a huge amount of floorspace, that the military loved the idea of using it for various crazy projects.

There was one for testing a Soviet airborne laser and one was tested to be the equivalent of America’s E-6B mercury. It had space, it could be refueled inflight, and it was “off the shelf.” Eventually, saner generals realized that the sheer amount of fuel it would need to stay airborne on long missions was impossible to carry along with mission-specific equipment.

What were some of these IL-86s, you ask? Well, one had two decks with a 600 passenger capacity. Most amazing of all, it still seemed to have been powered by Kuznetsov NK-8s. Eventually, engine technology advanced, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the closest thing to the original IL-86 and Aerobus brief took flight; the IL-96.

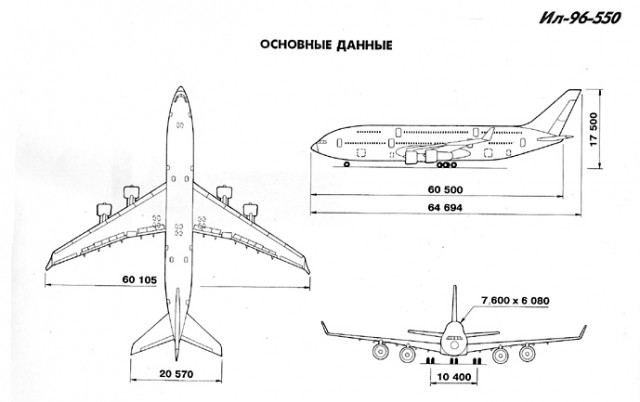

While not the twin deck IL-86 with NK-8s, this was the original IL-96. Pitched as a high capacity IL-86 with bigger engines. Drawing by: Ilyushin.

Sometimes, I sit back and daydream about what would have happened if the L-1011 deal had gone through. Would I have flown to Pyongyang on an Air Koryo, Voronezh-built, Tristar? Wouldn’t that have looked amazing!

Now there’s an interesting alternate history.

just found on net,,,rosavia/ecojet from russia…interesting plane…

very interesting planes, although never flown

Very interesting article. It says that Lockheed sent an L-1011 to Moscow in 1974. Jimmy Carter wasn’t elected until November 1976 and didn’t take office until 1977. What were the Nixon and Ford Administration’s reaction to the proposed deal? And why did the Soviet Union need US authorization to buy an engine, the RR RB-211, manufactured in the UK? The above is a good story, and probably mostly true, but the politics mentioned make no sense, based on the dates, and that little problem about the British building the RB-211 with composite fan blades, not the Americans.

Live cam sex and chat through Webcams. Get started now for free

Article is poorly written, replete with errors of the FACTUAL kind and requires editing.

Other than that, it tells an interesting tale. Editing required!