Socata TBM 900 N900KN in better days – Photo: scotch-canadian – www.airport-data.com

Throughout the past 35 years, there have been several high-profile cases of aircraft crashes due to cabin depressurization, with one of these being an airliner. Aircraft pressurization is actually a pretty simple process on modern aircraft, and is almost always computer-controlled. Aircraft are pressurized through the use of compressed air that is either supplied by bleed air tapped off of the engines, or, as in the case of smaller piston engine aircraft and the Boeing 787, by a compressor on board the aircraft.

This pressurized air is regulated through the means of outflow valves that help to maintain cabin pressure to the design limits of the airframe. Most commercial aircraft are pressurized to an altitude of 8,000 feet, with the main exception being the 787, which is pressurized to 6,000 feet. In very rare cases, however, things go wrong, as was experienced in the tragic loss of a Socata TBM 900 off the coast of Jamaica on September 5th.

The Boeing 787 is designed to be pressurized at 6,000 feet

At roughly 10:00 a.m. Eastern time, TBM 900 N900KN, the first of its type to be delivered, was last heard from by ATC as it made its way from Rochester, NY to Naples, FL. Approximately 40 minutes later, two F-16s from McEntire Joint National Guard Base in South Carolina intercepted the aircraft and found all of its windows frosted over, and according to audio from the fighters, they could see the pilot slumped over in the pilot’s seat, and reportedly he could “see pilot’s chest moving, hopes he regains consciousness as unresponsive plane descends.”

It is not known at this time what exactly happened, but the frosted windows are one indication of a rapid depressurization of the cabin. The aircraft continued on the last heading programmed into its autopilot for roughly 1,200 miles before finally running out of fuel. Tragic as it is, this type of incident is not unheard of, as it has happened before with very similar results.

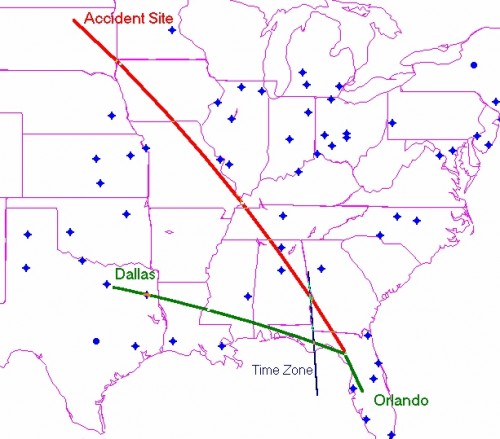

Flight path of N900KN. Planned course marked in red – Image: Flightaware.com

The most well-known incident of inflight depressurization occurred on October 25, 1999. Pro golfer Payne Stewart was a passenger on a chartered Learjet 35 (N47BA) en-route from Orlando to Dallas when ATC lost all contact with the aircraft.

Upon interception by a USAF F-16, the aircraft was found to have all windows iced over, with no sign of the crew or passengers. The plane continued on a straight course across the midwestern United States prior to running out of fuel over South Dakota and crashing. In the accident investigation, the National Transportation Safety Board report detailed that the aircraft had received maintenance many times over the preceding several months for pressurization issues.

The report also noted that post-crash analysis found that the engine bleed air system appeared to be functioning normally. The most logical cause for the incident would have either been a cabin pressure specific component failure, or a breach in the airframe.

According to the incident report, “a period of as little as 8 seconds without supplemental oxygen following rapid depressurization to about 30,000 feet may cause a drop in oxygen saturation that can significantly impair cognitive functioning and increase the amount of time required to complete complex tasks.” In essence, the crew would have had little time to don their emergency oxygen masks prior to succumbing to the effects of hypoxia and being unable to function, although they would still be alive, barely.

Another well-known and documented case of pressurization issues with an aircraft was Helios Flight 522. However, this crash was not a result of inflight depressurization; rather, it was a cascading result of errors and the effects of hypoxia on the pilots.

On August 14, 2005, Helios 522 departed Lamaca, Cyprus for Athens, Greece, and almost immediately the crew received an aural alarm along with warning lights indicating that the cabin was not pressurized as the plane passed through 10,000 feet. The captain immediately contacted Helios maintenance control to diagnose the problem and correct the issue.

Prior to departure from Cyprus, the plane was worked on by a mechanic for noises coming from a door, and the plane was pressurized on the ground for troubleshooting. In order to accomplish this task, the pressurization had to be selected to manual, and upon completion, the mechanic failed to reset the switch to auto.

When the crew performed their preflight checklist, they failed to catch it. When the captain was put in contact with the mechanic, he was asked if the pressurization control switch was in manual or auto, however, by this time, hypoxia was already taking its toll, and the captain and first officer were sure they had another issue and ignored the question.

The result was nearly the entire crew succumbing to the effects of oxygen starvation, and being rendered unconscious. However, when the plane was intercepted by Greek F-16s, the pilots of the fighters noticed a person working their way forward in the cabin. It was later discovered that a flight attendant was able to don an oxygen mask and slowly make their way to the cockpit. While the attendant happened to be a licensed pilot in England, he was unfamiliar with the 737 systems, and could not recover the plane. The plane crashed in Grammatiko, Greece, following fuel starvation.

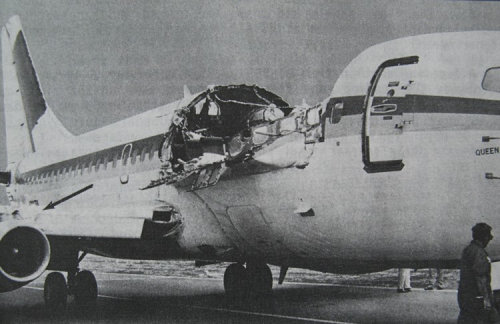

While issues like these are rare, they tend to make headlines because of the way they occur. In the past 35 years, there has been six major cases of pressurization issues being a major contributing factor in crashes, and only one of those has involved an airliner. For successful stories of incidents like this, one only has to look at the Miracle Landing of Aloha Flight 243.

Just after leveling off at a cruising altitude of 24,000 feet, the Boeing 737-200 experienced rapid depressurization caused by metal fatigue in the fuselage skin, causing a roughly twenty foot-long section of the upper fuselage to rip away from the aircraft. Miraculously, only one one person was killed, a flight attendant who was sucked from the aircraft, and while there were serious injuries to many of the passengers and crew, all the rest survived. It was shear luck and the skill of the pilots that brought the plane to a safe landing.

As mentioned earlier, cabin pressurization is supplied by compressed air taken from either bleed air off the engine’s compressor core in the case of a turbine engine, or through an air pump, whether it is engine driven or electrically driven. It is a simple system in principle, and rarely fails with disastrous results, if it ever does.

Was United 811 a pressurization issue (that’s the incident where the forward cargo door blew out in flight)

UAL811 was not related to pressurization issues directly, but rather due to a combination of faulty door latch mechanism and bad design, in a way similar to the problems the DC-10 had, but just not as severe. However, while it did result in a rapid decompression event, and resulted in more fatalities (9) than the Aloha,, it was not as severe it comes to structural damage to the aircraft, especially since N4713U was repaired and placed back into service less than a year later.

ahh that’s right … I knew that the pressure differential blew the door off but I couldn’t remember if it was that solely or the locking mech. failing

Did they decide that the Cirrus incident over Virginia a few weeks back was pressurization-related also?

I have yet to hear a probable cause on the incident with the Cirrus. Since the Cirrus is an unpressurized aircraft, it would not be a pressurization issue, but it could have been a problem with the pilot’s oxygen system, or it easily could have been medical related. We will probably never know.

You’re right, I couldn’t remember if the Cirrus was pressurized or not.

Very good article! keep it going!

United just had to make an emergency landing into Chicago flight 1610 from Denver due to an engine bleed, how dangerous is this engine bleed? I do know the cabin was extremely hot and the captin made an announcement about not wanting people to start passing out, was that due to the heat or pressurization?

I am not too sure how the bleed air system on the 757 (the type that was flying UAL1610 on the 14th when this diversion occurred) works, but if there was a temperature issue in the cabin, and a bleed air issue, there was most likely a problem with one of the air conditioning packs, which use the bleed air to regulate cabin temperature, as well as pressurization. If they had a problem with a pack, and there are 2 onboard the 757, it could very possibly cause very hot conditions in the cabin, and in that case, the captain made the right call to divert to a nearby airport, which is also one of United’s major maintenance bases, to have the plane checked out and repaired.

typo

in the paragraph about aloha, you write “It was shear luck …”

it should read sheer luck.

great post

Although the reports of Air Asia Flight 8501 seem to report the flight exploded before impact i think the reporters are misinterpreting the official in the quote or the official misspoke in his second language English. He might have been trying to say the flight exploded then went down. Postulate the pressurization to 8000 feet and some malfunction in the pressure adjusting system (slow response or non-response). The plane is climbing in a thunderstorm and hits a 36000 foot “air Pocket” or strong forceful updraft and then a sudden air pocket. If the pressure limits on the cabin are near limits that could be enough to explode. The press photo of the image looked like an exploded drink can.