Science and sugar are two sides of the same coin – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

Recently, I shared some background on NASA’s airborne telescope; the 747SP called SOFIA- the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy. The background is interesting enough, but getting to fly on it was taking this to the next level.

One thing I was not expecting was a bunch of sugar onboard. On top of it recently being the Mission Director’s birthday; myself, the public affairs officer for the program, and the outreach director all brought bags and boxes of empty calories. Delicious, empty calories. Science is hard work, and sugar is a necessity. Doubly so when the Mission Director insists that she is not taking any of the cake home with her.

This is where SOFIA is normally parked; from this angle you can better see the telescope fairing – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

Okay, beyond being a pirate ship full of candy, then? How about a lot of familiar bits and pieces from a number of different airlines?

You ever been on a Lufthansa A300? What about a Classic United Airlines 737?

I miss the old United fabric – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

There are little hints from past airline involvement all over the aircraft.

How about this?

The computers on board SOFIA run various flavors of Linux and OS X – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

That’s the telescope operator’s station, and behind it is a conference table. Adjacent is an identical workstation for the scientists collecting data. Behind their station is the observer’s station where official NASA guests sit and either conduct some of their own experiments or piggyback on the other data collection.

Of course, none of this would work without the telescope and FLITECAM.

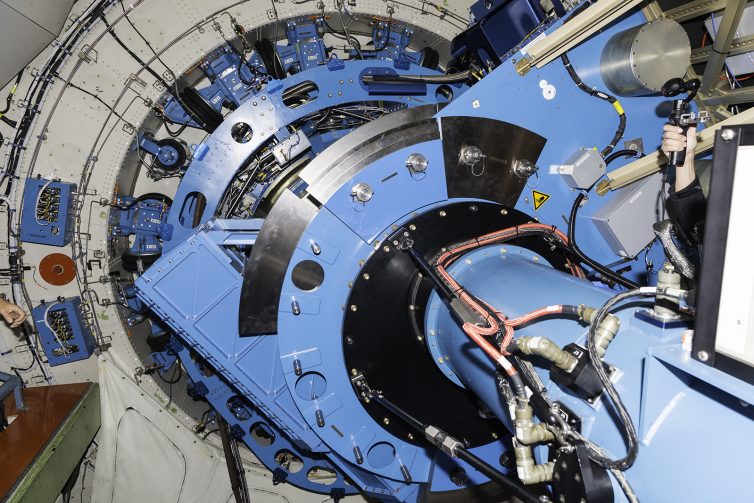

As the photo better illustrates, you can see the processing and balancing parts of the telescope. The remaining parts have to cross the pressure bulkhead. – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

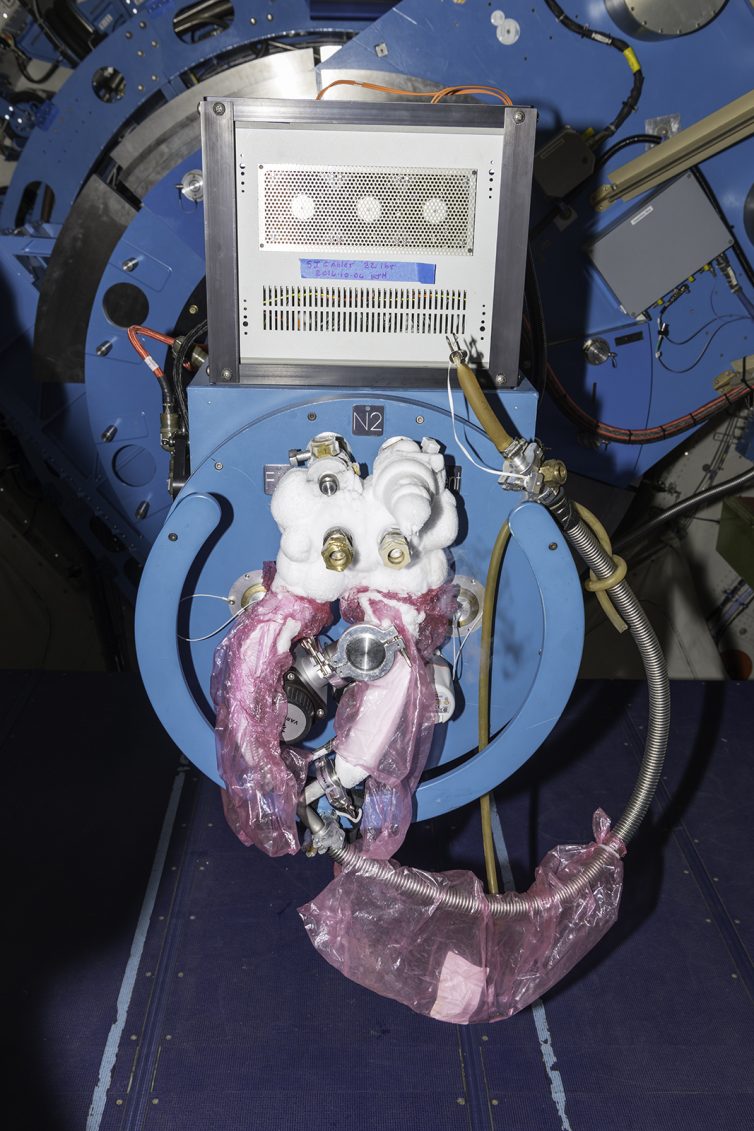

To show you how much science is going on, FLITECAM is even cooled by cryogenic liquids. The vents are covered in ice and there is a constant emission of steam from coolant boiling off.

Precision instruments require precision coolant. Cryogenic fluids are so cold they can cause the water vapor to freeze on the vents. – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

SOFIA doesn’t usually go out with 33 people on board like our flight. That number included the flight crew, the mission directors, the scientists, and the educational outreach observers who had their own experiments beyond sitting at the observer’s station.

If you are not sitting in Business Class up front, you must don a headset. Despite being a standard pair of David Clarkes, they use a series of strange adapters to hook into plugs the likes of which I have never seen. Clearly, there are some grounding issues as well as stuck mics resulting from the push to talk – but they do their job.

Now, it’s been at least 20 years since I had flown on something with JT-9 engines – but the conversations running through the headsets were hilarious. I had to keep one ear on. Start-up is not like that on your ordinary 747. In fact, it’s not even SOP for a 747SP.

You start engines three and four on SOFIA, then taxi using only them. Why? Keeps the dust out of the cores. What also shocked me is just how loud everyone thinks the ramp is, then how loud everyone thinks the plane is. There are earplugs everywhere, people were wearing earplugs during start-up. It wasn’t that loud at all. A little higher pitched than an RB211, but not really deafening. It’s a pleasant whine. Sounds a lot like the engines on a P&W-powered 767, to be quite honest.

%CODE1%

Even after we approached the hold short line for Runway 25 and turned on the outboard engines, things didn’t seem much louder. DC-10 or MD-11 kind of volume. Probably a little louder outside, but nothing like how those unfamiliar with classic airliners made it seem!

Around 42 seconds later, we were off the 12,001 foot runway 25 and climbing. It was a smooth takeoff, despite the strong surface winds. As we climbed out over Arizona, the seatbelt sign was turned off and the flight began to transition from the command of the pilot to the mission director.

I didn’t feel the telescope door open, because no one does. While the door affects fuel burn by 2% in cruise, if you need to seriously knock the aircraft out of trim to focus on something; it is theorized you can impact the fuel efficiency by up to 30%; while still not feeling any effects.

All you see or know about the door opening inside is a little grey panel being raised on a screen.

Once it’s open, you can see what the instrument sees. That means a lot of things whizzing past on monitors, and the “ghosts” created by ice and debris either being eliminated or fade away. Speaking of the ghosts: they exist because budgetary reasons prevented NASA from being able to pre-cool the mirror prior to opening the door.

Unfortunately, shortly after the door was open, we were over Colorado where there was a moisture-rich low. That, combined with the Rocky Mountains, meant turbulence.

The only reward from the turbulence was watching the telescope stay perfectly still whilst we moved around it. I wanted to take a movie, but I was facing forwards. Take my word for it, it looked insane. This wasn’t even bad turbulence — especially by Rocky Mountain standards. It was odd how concerned everyone seemed about the duration, even though there was no risk to our ability to collect data.

Worse, with the seat-belts on, I couldn’t walk to the fridge and get my burrito. Donuts would have to suffice. Once the turbulence stopped around 37,000 feet, it was time to poke around the aircraft while it was live.

This is the instrumentation area of SOFIA; in the distance is the telescope operator’s panel. The man in the hat is rockstar astronomer Dr. Ian McLean. I was starstruck! – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

The first point of interest was the actual FLITECAM station. Currently commissioned by Dr. Ian McLean, the FLITECAM team had begun gazing upon the Draco constellation to make sure everything was in order. It was time to climb the spiral staircase and visit the flight deck.

This is SOFIA’s flight deck in action; not pictured is the flight engineer – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

The captain that night had a long history of flying exotic 747s, while the first officer used to work at Boeing. In fact, he flew out of BFI. We realized that we used to constantly annoy each other over on taxiway B2. Small world! The flight engineer had a long career with United before coming to NASA. They also have a preference for Lightspeed headsets. Good.

Don’t worry, you can fly with one oil quantity indicator INOP – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

This is where I learned about how small the margin is when you are flying a 747SP above 40,000 feet.

While we cruise at Mach 0.85, the onset of buffet is mach 0.82. While overspeed on a normal SP is around Mach 0.92; overspeed on SOFIA is said to be Mach 0.87. With the air temperature at -53ºC, at 41,000 feet that’s not a big difference. On top of that, even though the lapse rate was nonstandard, it’s still really cold. You never want jet-A to go below -42, so there are temperature sensors in the tanks.

Keeping the fuel warm wasn’t too precarious this flight, but here is how the flight engineer does it anyway. First, you can turn on the heaters. On top of that, you can pump the fuel around. This might not get everything, especially the tanks that are loaded in the farthest edges of the wings that are kept relatively heavy to keep wing-flex within range.

This may seem counterintuitive, but friction (even at that temperature), from going faster can heat up the leading edges of the wings. This can provide just enough of a thermal bump to keep the jet-A nominal. Wild, right? When UA used to fly over the poles in the SP, they had to spend a lot of effort and money doing that.

Apparently it’s even more of a challenge for NASA’s DC-8 on antarctic missions – but now I just want to see that for myself! The flight engineer also told me that the leading-edge de-ice system on the DC-8 can help warm the fuel. So cool!

This DC-8 – Photo: Bernie Leighton | AirlineReporter

To give you an idea of why airlines don’t fly the SP anymore, we took off with 250,000lbs of fuel. For planning purposes, one assumes 22,500lbs burned per hour. That means we burned about 219,000lbs of fuel over our flight (over $40,000 in fuel).

What SOFIA does have is a glass cockpit and glass secondary engine instrumentation on the flight engineer’s panel. Reducing crew workload was not the primary goal, though that is a useful benefit. This was done because it is getting nearly impossible to find viable spares.

Pratt & Whitney has done the same on their SPs, but they use the cockpit power bus from the 767 to add a little more headroom in their system. Whether it’s needed is a matter that became hotly debated during my time up top. (Personally, I think you do)

This brings me to the next challenge facing SOFIA: they are only funded until 2018. They presume that with more funding, they can keep going until 2033. That’s if everything goes perfectly. A problem is NASA only has twelve more JT9D-7As and that’s including the ones they got from purchasing the Fry’s aircraft.

There was discussion with respect to putting a different engine on; but this isn’t a DC-8. A 747 would need an almost entirely new wing and no one has that kind of money lying around. To top all that off, it was amazing to watch the CRM in action. Every new altitude, the flight engineer would work out new speeds that were safe for us to fly. This would be written in grease pencil on a yellow card.

SOFIA lifting off – Photo: NASA

Did I mention SOFIA is cold?

It makes sense, don’t get me wrong. Electronics work better with good cooling. Combine that with being at 43,000 feet and the latent mechanics of heat transfer also play a part. Bring a sweater, and if GREAT (the German Receiver for Astronomy at Terahertz Frequencies) is going, bring a hat and gloves.

The rest of the flight was a breeze, though I understand the FLITECAM software went nuts somewhere around the last two targets. Oh well, that’s science. The Mission Director still called it a success!

Beyond that, I just have to marvel in how amazing it is to fly on an observatory based around a 747SP in 2016. It also amazes me how smooth a flight can be when you optimize for avoiding turbulence, rather than cost.

Comments are closed here.

Very Cool! Though I don’t understand why they don’t put engines from a 744 on it. I would assume their surplus because many airlines are retiring them.

Best story on Airliner Reporter yet….