Success! I finally earned my private pilot certificate!

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

After a year and a half of concerted effort, I’ve finally completed my initial training and earned my private pilot certificate in early November. It’s a great feeling!

For those who’ve been following along on my adventures at Galvin Flying, it’s been a long process of successes and setbacks, many of which were weather related because I live in the Pacific Northwest, where the local joke says that it only rains once a year it starts raining in late October and stops raining on July 5 (it always seems to rain on July 4).

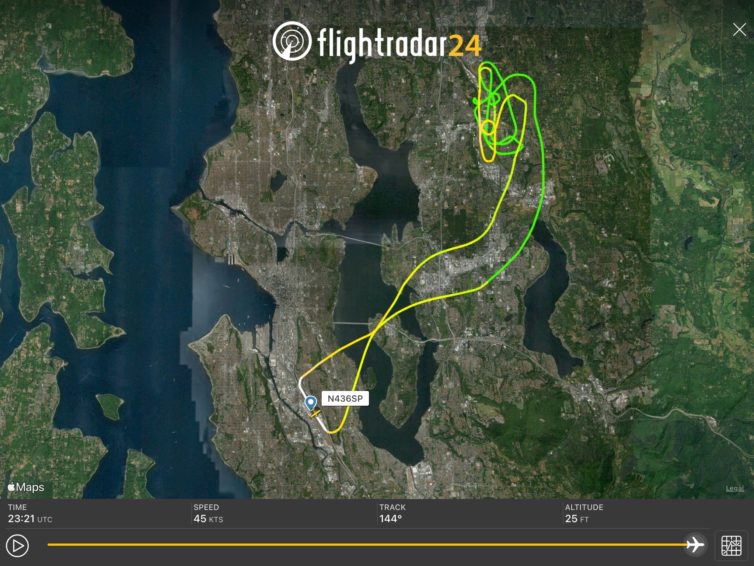

In case you ever wondered what the track of a checkride looks like, here you go. Screen capture courtesy FlightRadar24

Anyway, I did several mock checkrides in the weeks leading up to the actual FAA one, and had to complete Galvin’s end-of-course checkride before that. The end-of-course checks are designed to be more difficult than the actual checkride to ensure that pilot candidates are as prepared as possible.

The FAA examiner, also known as a designated pilot examiner or DPE, selects from a long list of information and flight maneuvers for the actual checkride known as the Airman Certification Standards. The check airman who oversees the end-of-course checks runs through the entire list to be sure you’re ready.

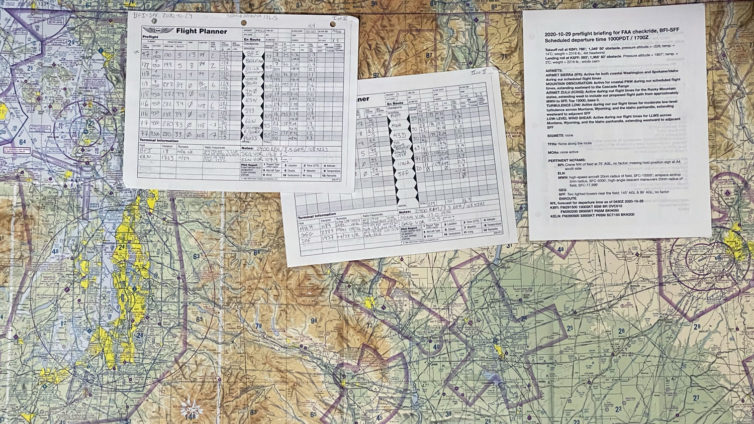

Both checks consist of a lengthy ground session to review the rules, regulations, and related information found in the federal FAR/AIM manual, plus aviation decision making, route finding, and so on. Then a flight to be sure you can fly all the required maneuvers to standards. The evaluations also require a very thorough flight plan to a randomly-assigned airport.

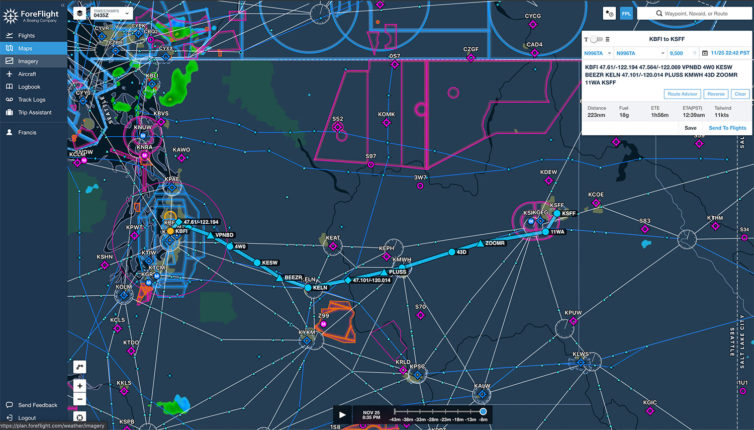

My FAA checkride assignment was to do a detailed VFR flight plan for the 200+ miles from Boeing Field in Seattle to Felts Field in Spokane, a route which included mountain flying. You don’t actually fly the whole route on the checkride; the planning is done primarily to assess your route-finding, weather assessment, and planning skills, although you do fly the first couple of legs of your plan on the checkrides.

My assigned aircraft for the checkride was this fine C172SP

If successful in the classroom, then it’s off to the flightline, where you’re evaluated on everything from how well you perform the pre-flighting of the aircraft, to your decision as to whether it’s safe to fly that day. Once that’s done and you’ve received taxi clearance and completed the pre-takeoff run-up and checklists, it’s off to fly the first couple of legs of your assigned flight plan. That went well, so I was asked to divert to a randomly-selected local airport, in this case Paine Field (KPAE) in Everett, Wash., which is designed to test your ability to create a new flight plan while in the air, along with being able to pinpoint your current location on the paper chart.

A Seattle sectional chart, the paper flight logs, and the first page of the briefing I wrote up for my checkride

Candidates are allowed to use any technology available for planning, so I roughed out the route in ForeFlight, which is a most excellent flight-planning tool for pilots. Examiners are notorious for “failing” any technology a pilot candidate is using, which means they’ll tell you, typically at a crucial moment during the flight, that whatever tech you were using just broke and disallow you from continuing to use it, which sends you scrambling for your paper charts and paper flight plan.

So, it’s safest to primarily use the paper charts and use the tech as the backup for the checkride, as you are also responsible for being able to competently use whatever equipment happens to be installed in your particular aircraft.

This was my proposed route from Seattle to Spokane for my checkride. Screenshot is from ForeFlight

The DPE asked me to perform several maneuvers, including slow flight, power-off and power-on stalls, turns around a point, and steep turns. After that, I had to put on a hood that restricted my vision such that I couldn’t see out the windows and could only see the instruments, then I was asked to perform several accurate course and altitude changes using only the instruments while maintaining proper control of the aircraft.

We then returned to Boeing Field, where I had to perform several different types of landings and takeoffs – short field, soft field, and normal.

A checkride is not considered to be complete until the aircraft is properly parked on the ramp and the engine-shutdown checklist is complete. It was at that point the examiner turned to me and said, “congratulations – your checkride was successful and you’re now a pilot.”

So, I’ve already started getting checked out in the Diamond DA-40 with the G1000 glass cockpit; next step will be to begin instrument training after the first of the year

Less than a week after that, I started training to fly the Diamond DA-40, a plane I’ve been admiring all through training. Weather and schedule conflicts had conspired such that I’ve still not gone flying on my own as a certificated pilot, but that’s gonna happen soon, not to worry, … once this rain lets up.

Congrats Francis!

Thanks, Steve!

Congratulations, Francis! The DA-40 is a fun change of scenery compared to a C-172! Safe travels 🙂

Thanks, Jillian! I”m definitely enjoying the DA-40″s bubble canopy and low wings.

Congratulations! These have been a lot of fun to read and encouraging for someone who keeps saying “I’ll get around to it…someday.” Your turn work in that FR24 capture is pretty much smack-dab over where I grew up! Keep the stories coming when you’ve got the time to write ’em.

Thanks for reading the series, Matt! Hope you get to fly one day, too. I”m definitely planning to keep the stories going as I progress through instrument training.

Congratulations!!

Thanks, Mark!