An El Al 767 at Zurich airport – Photo: Aero Icarus | Wikimedia Commons

Ask any self-respecting airline geek which airline was the first to introduce commercial trans-Atlantic twin-engine services, and you’d probably get an answer like TWA, American, or maybe Air Canada. The surprising answer? Plucky little El Al, the fiercely independent but resource-challenged national airline of Israel. How did that happen?

Never shy in taking on a new challenge, El Al has built a reputation on pioneering industry breakthroughs ’“ a non-stop distance record on the JFK-TLV proving flight with a Bristol Britannia in 1957 (5,760 miles). A trans-Atlantic speed record on the 707 JFK-LHR segment in 1970 (7 hours, 57 minutes). The ultimate ’œhigh passenger density’ 747-400 operation in which a staggering 1,122 Ethiopian refugees were safely (if not so comfortably) evacuated from Addis Ababa to Tel Aviv in 1991. And a set of remarkable COVID repatriation flights in 2020.

In 1983, El Al took delivery of the first of four 767-200s from Boeing. The first two airplanes were the standard range models (4,270-mile range). The second two airframes were extended range (ER) variants, equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7R4E engines, enabling a range of 5,610 miles.

By 1984, the FAA was actively working with several operators to implement new overwater operational approvals for twin-engine operations ’“ what would become known as ETOPS- Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards. But the old rule ’“ that the flight had to stay within a 60-minute radius of a suitable landing site was still in effect.

It’s hard to wrap our heads around this today when we can fly 19 hours with up to 330 minutes ETOPS. But the notion of twin-engine oceanic operations was new stuff back then. A lot was unknown. An inflight engine shutdown would make the remaining engine work harder. Could it handle the stress? Could the one remaining generator or hydraulic pump reliably perform? And simply relying on the APU to cold-start at cruise or for the ram air turbine to properly deploy was not sufficient. Alternate airport requirements were more strict and a host of crew-training, equipage, and certification requirements made the very proposition of viable commercial ETOPS operations a daunting task.

What was clear was that the economics of twin-engine operations was quite compelling. The cost savings of operating a 767-200 with 190 passengers compared to a 370-seat 747 on a typical trans-Atlantic route was in the range of 45%. Fuel and crew costs (including the new two-person cockpit of the 767) accounted for the majority of the trip savings.

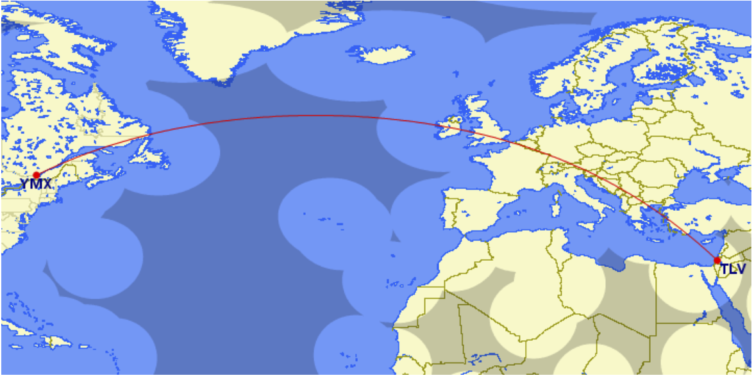

Having trialed its two ERs on shorter European runs from Tel Aviv, El Al was ready to exploit the 60-minute rule for commercial service from North America. On March 26, 1984, El Al became the first airline to offer commercial ETOPS flights, operating a 767-200ER (4X-EAC) from Montreal to Tel Aviv. The non-stop route, in compliance with the 60-minute rule, took 11 hours and 8 minutes.

El Al’s first ETOPS flight was from Tel Aviv to Montreal on March 26, 1984 – Image: Great Circle Mapper

Based on the early success of the Montreal route, El Al added more ETOPS flights the next year offering 767ER service on the following routes:

- Tel Aviv ’“ Amsterdam ’“ Chicago ’“ Los Angeles (LAX)

- Tel Aviv ’“ Amsterdam ’“ Montreal

- Tel Aviv — Amsterdam ’“ New York (JFK) ’“ Miami

El Al’s early transatlantic routes were groundbreaking – Image: Great Circle Mapper

Ultimately, the airline would achieve 120-minute ETOPS approval, allowing more flexible routings on the North Atlantic runs.

El Al’s achievement was groundbreaking ’“ both technologically and psychologically. There was a lot of resistance to the idea of twin-engine oceanic flights back then ’“ from the International Federation of Airline Pilots (IFALPA) to former FAA Administrator Lynn Helms. Ultimately, technology ’“ and economics ’“ would prevail.

TWA was quick to follow El Al’s ETOPS example – Photo: Ralf Manteufel | Wikimedia Commons

El Al’s exploits were closely monitored by other airlines, eager to cash in on the favorable twin-engine economics. TWA had ten 767s on order at the time, and was working with the FAA to secure 120-minute ETOPS authority, which would allow for more direct routings from its St. Louis hub. TWA launched trans-Atlantic ETOPS flights the following year on its Boston ’“ Paris route and would go on to build a network of 767 routes from St. Louis and New York (JFK) hubs. American and Air Canada were quick to follow. The floodgates were opening.

Air Canada quickly sought ETOPS certification for its 767s as well – Photo: Michel Gilliand | Wikimedia Commons

Today, the vast majority of flights across oceans are performed by twin-engine airplanes. Few were the visionaries who could foresee that development in the early 1980s, when the very notion of twins across the ocean was controversial. But the contemporary dominance of twin-engine intercontinental flight came about only through three decades of patient, deliberate development in commercial ETOPS operations ’“ punctuated by the bold exploits of a few early movers. So, next time you board a 787 for Frankfurt or A350 to Hong Kong, you might just tip your hat to that plucky airline from Israel that started it all.

Not gonna lie – it’d be great if El Al would do a heritage livery like this – Photo: Michel Gilliand | Wikimedia Commons

Thank you for this great article.

I was lucky to be involved in the development of ETOPS rules from 1989 to the early 2000″. I joined when the limit was moving from 2 hours to 3 hours, then we had accelerated ETOPS, then ETOPS out of the box. In Europe, we had set-up a working group that operated in close liaison with FAA, Transport Canada and other authorities. The European group was multi-disciplinary and we had authorities, manufacturers, pilots, maintenance experts in the group. We used a total system approach. I have very good memories of the group and wish to thank its members for their cooperative attitude. I think that ETOPS is a rule that have had a significant impact on commercial air transportation.

Great story!

Tiny nitpick – it feels weird to hear about “JFK airport” in reference to flights in 1957 — at the time it was called Idlewild airport, with the airport code IDL.

So if the cost savings of operating a two-engine 767 with 190 passengers vs. a four-engine 747 with 370 passengers is 45%. . . . well, how much have you saved if you have to operate two 767’s to carry those 370 passengers? The cost would be 10% less for the two flights and you can haul 10 more passengers. Is this enough of a cost-savings to make it worth it? Apparently so. Am I missing something about airline economics?