On final for runway 14R at BFI in a Diamond DA-40 – this wasn’t from our mountain-flying day, but it’s too pretty of a photo to leave out of the article

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

The lousy Pacific Northwest early spring weather notwithstanding, I’ve made good progress towards learning both the Garmin G1000 instrumentation and the Diamond DA-40 aircraft. We recently got a decent break in the weather that allowed a flight from Seattle across the Cascade Mountains to Ellensburg for some basic mountain flying training.

Cruising westbound at 6,500′ over Snoqualmie Pass was an amazing experience – Photo: Katie Bailey

I’ve got about 10 hours in the DA-40 now, all but one of them with Carl, my ever-patient CFI. I finally felt comfortable enough with the plane to take it out on my own last week, even though Carl had deemed me ready to do that about five flight hours previously. I just wanted a bit more time with the plane, as it’s quite a bit different than the Cessna 172, especially in that it’s a lot faster and a bit fussier when it comes to controls, and it’s got a constant-speed propeller (also sometimes referred to as a variable-pitch propeller) that needs tending to via a dedicated control lever.

- Even though electronic tools like the G1000 and Foreflight on a tablet or phone make planning easy and safe, it never hurts to work it out on paper as a backup

- This was our route from BFI-ELN, over the mountains at 9,500′. Screenshot from Foreflight

- This was our low-level route through the mountains returning to BFI from ELN. Notice the less direct route. Screenshot from Foreflight

If you’ve been following this series, you’ll have read a bit about route-finding through mountainous terrain in my December, 2020 story about my certification checkride. There are, pardon the pun, mountains of information and classes available concerning mountain flying. Here in western Washington state we’ve got a large mountain range to both the east (the Cascades) and the west (the Olympics), so it’s pretty much required reading if you want to fly beyond the Puget Sound area. Flying over and through the mountains also requires different training than is needed for landing in mountainous areas, so I’ll be tackling the landings next as my post-certification training continues.

The lakes at the summit of Snoqualmie Pass are quite distinctive and make great visual navigation checkpoints – Photo: Katie Bailey

Route-finding through mountainous terrain is definitely about avoiding the granite, but it’s also about doing your best to make sure you have options if something goes wrong in the air. If you need to land in a hurry, for whatever reason – be it mechanical issues or being surprised by unexpected bad weather – you want options. So, both the outbound and return routes followed Interstate 90 over Snoqualmie Pass, which offered lower terrain, and a four-lane highway as an option for emergency landings, as well as a couple of mountain airstrips along the way. We flew the outbound leg at a higher altitude, and the return at a lower one to gain experience with both options.

Here we’re adjusting the autopilot to turn a a bit more to the left while passing over Snoqualmie Pass in Washington state – Photo: Katie Bailey

On a clear day with relatively smooth air, it was a glorious flight eastbound over the mountains at 9,500′, taking less than an hour to cover the 93 miles from Seattle to Ellensburg (which, for comparison, takes more than two hours by car via I-90).

On the downwind leg for landing at Ellensburg, Wash. – Photo: Katie Bailey

We practiced using the autopilot as much as possible, but it does require constant monitoring and adjustments to avoid clouds, while watching for other aircraft traffic, etc. Also, the DA-40 requires manually switching the two wing fuel tanks every 30 minutes to keep the load balanced, so watching for those alerts on the G1000 becomes part of your instrument scan.

Touching down on runway 29 at KELN – Photo: Katie Bailey

The outbound flight went by quickly. After stopping to stretch our legs a bit at Ellensburg, it was back in the plane to enter the new flight plan into the nav system and head back to Seattle, this time through the pass at 4,500′ to 6,500′ (south and westbound flights are at even altitudes plus 500′, north and eastbound at odd altitudes).

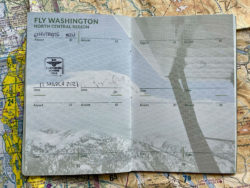

- The Fly Washington Passport program is super fun, encouraging the exploration of the 100+ airports in the state

- Finally got my first stamp in the north central region

While at ELN, we all visited the small mailbox outside the FBO containing the stamp for our Fly Washington passports. It’s a fun (and free) program to encourage pilots to visit airports in the state and log their adventures. If you’re a pilot (or have a pilot friend) in or near Washington state, I definitely recommend checking it out.

On short final for runway 32R back at KBFI – Photo: Katie Bailey

We had planned to fly at or below the tops of the mountain peaks traversing Snoqualmie Pass, but there was a fair bit of mountain-wave turbulence at 4,500′, so we climbed to 6,500′ into clear air – the DA-40 feels like it gets tossed around a bit more than the C172s in rough air. Mountain-wave turbulence happens on the downwind side of terrain, such as we experienced flying westbound into headwinds passing over the peaks. Mountain-wave turbulence and rotor waves are but two of the more uncomfortable/dangerous types of turbulence encountered in mountainous regions. Rapidly-forming clouds are another, especially when the temperature and dewpoint are within 3ËšC of one another, so very thorough weather awareness, both pre-flight and updating in flight, are essentials.

More to come about mountain flying and, hopefully soon, the start of instrument training.

Fantastic article, Francis! Mountain flying is undoubtedly challenging. Making sure you have options and an out for when something goes wrong is critical. I would imagine having the autopilot onboard the DA40 makes an immense difference in managing task loads!

Fly safe!

Thanks, Charlie! The autopilot is an amazingly helpful tool for sure, but it also has its own learning curve. It’s all great fun to learn and fly.