Written by Chris Sloan and originally published at Airchive.com on October 9, 2013

Editor’s note: Welcome to part one of our multi-part epoch on the fascinating history of the Boeing Everett plant. We will be rolling the series out over the next month, so sit back, grab a glass of your favorite beverage, and enjoy the read.

Nestled 22 miles north of Seattle in a woodsy suburb of Everett, Washington is Boeing’s sprawling modern miracle of an airliner factory; a place so massive, so technologically sophisticated, and so vital to the world’s aviation industry, it’s hard to wrap your head around it much less write an article about it. What began as the birthplace of the world’s first wide-body airliner, the iconic Boeing 747, is, as of the end of July 2013, the site where a little over 50% of the world’s wide-body aircraft have ever been produced. Indeed, out of 6,746 aircraft produced by Airbus, Lockheed, Douglas, Ilyushin, and Boeing combined; a staggering 3,715 have been produced at Boeing’s Everett plant.

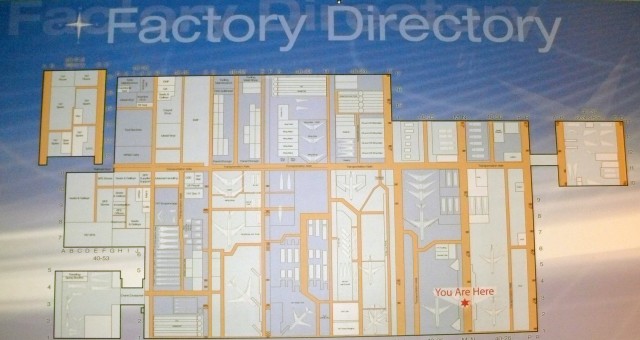

Nearly every Boeing wide-body airliner ever built, the 747, 767, 777, and 787 has been produced here in a complex known for its superlatives: It is recognized by the ’œGuinness Book of World Records’ as the largest building in the world by volume. Each factory door is the size of an NFL football field, and speaking of football ’“ 75 NFL fields could fit within the factory footprint. To this day there are only two such factories in the world where wide-body jet construction occurs from beginning (wing spar load) to end (final delivery): Boeing in Seattle and Airbus in Toulouse, France. Boeing’s North Charleston, SC facility and Airbus’ Hamburg facility are used for final assembly of wide-bodies but much of the major component fabrication such as wings and tails are done off-site.

An early design model of the Boeing 747 at the Boeing Corporate Archives. Image by: Chris Sloan / Airchive.com

The Beginning of a Behemoth

The story of Boeing’s modern marvel officially began in 1966 as Boeing began evaluating locations to build the Boeing 747 and the Air Force’s new large scale transport it was bidding for, the CX-HLS (Heavy Logistic System). Boeing lost the bid to Lockheed, ina design that became the C-5 Galaxy. In March 1966, the Boeing 747 was given an official green-light by Boeing’s board after Pan Am’s Founder and Chairman Juan Trippe signed an order for 25 747s valued at $25 million apiece.

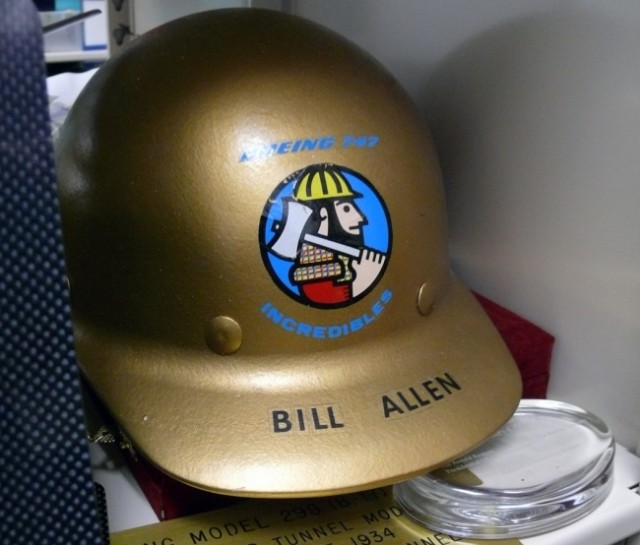

Boeing would have less than three years to build a factory out of the wilderness, and at the same time build the world’s largest jetliner to meet the late 1969 delivery targets. Around time of the official April 13, 1966 announcement Bill Allen, the legendary CEO of Boeing famously said, ’œWe are betting the company. The risks of the 747 are several times greater than in any of our previous commercial ventures.’

Boeing’s Bill T. Allen’s actual construction hat from the Everett site bearing the words ’œThe Incredibles’.

Image: Chris Sloan / Airchive.com

This seemingly impossible task would earn those involved the title of ’œThe Incredibles’ led by the legendary Joe Sutter. He was quoted as saying ’œThe main risk was the tremendous amount of money required to develop an airplane of that size, with all that new technology. Boeing’s investment in research and development, tooling, manpower, and an entirely new manufacturing site at Everett totaled more than $1 billion by the time of roll out, a sum greater than the company’s net worth.’

The company concluded that the final assembly facilities at Renton and Boeing Field were much too small and busy to accommodate a project of this nature. A number of locations were considered including San Francisco, Colorado, and Georgia; with the rural and difficult to access Everett area initially not even placing in the top five. Despite the political advantages of California at the time, and the lower-cost labor to be found in Colorado and Georgia, Everett held the edge in Allen’s heart and also his head. Boeing’s skilled Pacific Northwest aerospace workforce brought the expertise to get the job done.

Boeing’s Everett Facility at Paine Field photographed from the air in 2009 with runway 16R/34L on the left side. Image: Boeing

A small airport named Paine Field (often called Snohomish County Airport, or PAE) meant Boeing wouldn’t have to build its flying infrastructure completely from scratch. Dating back to 1936 and used by the Army and Air Force, PAE just happened to have a 9,100 foot-long runway (16R/35L) that is still used today for most Boeing test flights and deliveries.

The Boeing relationship with the Everett community didn’t begin with the 747. During WWII, Boeing operated two facilities in Everett to provide subassembly support for the B-17s being built in Renton, including work on bulkheads and the radio operator’s section. In 1956, the B-52 and KC-135 jigs and shipment fixtures were moved to Everett. Two-hundred-eighty-three employees from the Seattle Boeing Field and Renton plants were transferred to Everett along with 70 new employees hired locally. These original manufacturing facilities were located at the Everett-Pacific Shipyard. Boeing was even honored with a celebration called ’œBoeing Week’ in 1957. Boeing President William M. Allen attended a special Boeing Week banquet, which had an impact on him.

In June 1966, Boeing purchased 750 acres on the northeast side of Paine Field. This was not without its challenges as many long-time rural landholders didn’t want to leave. Many others became quite opportunistic when real estate agents representing Boeing swooped in with open checkbooks. Reportedly one small run-down property appraised at $4,700 was finally sold for $50,000.

Almost immediately an army of construction workers descended on the area, clearing the heavily wooded and rolling land. They blasted hillsides and filled in valleys. Most impressively, a spur of railway was hacked through the dense forest from the Great Northern railroad. More than 1.25 million cubic yards of dirt were moved to create the track bed, which climbed from 20 feet above sea level to the western edge of the Everett site at 540 feet, making it the 2nd steepest standard gauge railroad track in the whole country.

Over the next few months more than 2,800 workers and 250 subcontractors withstood everything mother nature could throw at them: windstorms, mudslides, 67 straight days of a deluge, and then snowstorms. The three main 300 foot X 1000 foot assembly bays began to appear from the ground in the fall of 1966 and by November 1966 the roofs were completed.

The idea was that the 747 prototype would be built on the actual production assembly line. The initial aircraft build and assembly happened as some of the tooling and building were going up around it. In May 1967, most tooling had been set-up with most subcontracting parts arriving throughout the summer in what became known as the ’œAluminum Avalanche’. In September 1967, the wing skin / stringer riveting machine was loaded for the first time, marking the start of wing build and official beginning of gestation of the very first Boeing 747.

At the time of completion in 1968, the original building measured 42.8 acres (1.9 million square feet) and 205,600,000 cubic feet in volume, instantly becoming the world’s largest building by volume. Remarkably, the Boeing factory was so capacious that it began generating its own weather systems. A then state-of-the-art circulation system had to be installed because clouds, the product of accumulated warm air and moisture, were forming inside. Then as now, there is no climate control system for temperature. In the winter machinery, body heat and residual heat from lights keep it warm; while in the summer, the doors are opened to cool the building.

Body join on an early Boeing 747 in the foreground. Note “The Incredibles” logo on the hangar door. Image Courtesy: Boeing

Unofficial tours for the public began in mid-1967, and by the end of the year 13,000 visitors had visited the facility. In response to the continuing demand, a Boeing Tour Center was established in 1968 and began a tradition of offering free tours of the Everett factory complex. During the first year, 39,401 visitors came to see where and how Boeing was building the 747. The tours have since remained one of the state’s most popular tourist attractions.

Extra: Boeing 747 Development Models at the Boeing Corporate Archives

Extra: Boeing 747 Historic Sales Brochures, Memorabilia, and Vintage Photos

Next In Part 2, we look at the troubled launch of the 747 and the crisis that crippled Boeing and nearly took Seattle with it.

Great article! Looking forward to the future installments. When I visited the Everett Boeing plant, one of the more interesting features was the tunnel underneath the plant that some Boeing personnel utilize as a jogging path.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article.

I will make sure to bookmark iit and return to read

more of your useful info. Thanks for tthe post.

I’ll certainly comeback.

Wrote more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seeems ass though you relied on thee video to make your point.

You obviously know hat youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to yourr weblog when

you could be giving us someting informative tto

read?