A model of the Shanghai Y-10. There is one extant copy, but it is very hard to get close to. – Photo: Shizhao

Today, the Chinese are building their second fully designed and built airliner, the Comac C919. However, back in 1980, they flew their first designed and built in-house airliner, the Shanghai Y-10 and it has an interesting (and quite short) history.

The Chinese aviation business after the 1949 revolution was, to say the least, lagging behind both the west and the Soviet Union.

The only aircraft assembled in China that was even close to the dimension and role of those built by their peers was the Xian H-6 a sinofied and license-built version of the Soviet Tu-16. Though the first Chinese medium bomber flew in 1959, no H-6 would ever be fitted with indigenously-designed engines. Chinese fighter aircraft followed along a similar trajectory, though their designers were offered a little more creativity in terms of adding differing body kits to license-built Soviet planes.

Something, however, was missing from the Chinese aviation industry. The skilled fabricators and support staff were there, but there was no real push for engineering talent- particularly in the civil market.

It is unclear how long the Shanghai Aircraft Research Institute had been researching a large, narrow-body passenger aircraft prior to receiving the government’s blessing in August of 1970, but the will was clearly there. Or at least, convicted Gang of Four member Wang Hongwen believed there to be. As a major player in the isolationist factions of the Chinese Communist Party, he was, in some ways, running astray of Mao’s latest internationalist gambits by trying to achieve a self-sufficient aviation industry. Let us ignore that, however.

An American Airlines Boeing 707. Image: The Boeing Company

Development of the Y-10, China’s effort into the civilian airline category was an arduous process. The aerodynamics, while similar to the Boeing 707, are not identical. Some sources would compare the fuselage length to that of a 720.

Many have seen designs that have come from Chinese and Soviet manufactures that closely mirror those that were already produced in the west. It would seem at first glance that the Y-10 could have been a copy from the 707 or the 720, but I am not so sure.

If you were to ask me, I think it is more likely that the design for the Y-10 probably came from the Soviet designed original Tupolev TU-156.

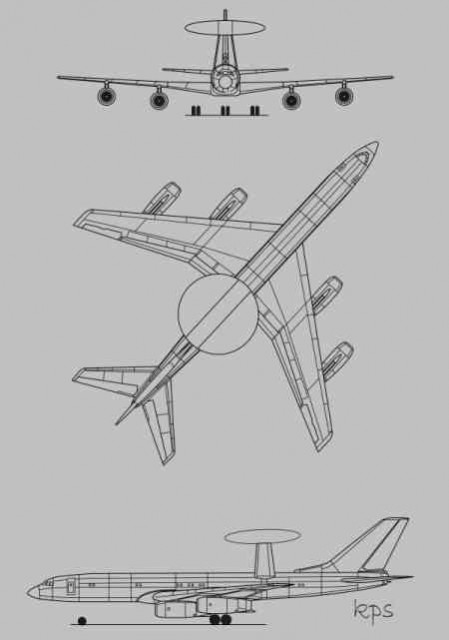

The Tu-156 (first version) Not a cryo-methane powered aircraft, but a four-engine 707-like beast. – Drawing: Konstantinos Panitsidis

The PVO (Soviet Air Defense Force) had wanted an all-jet aircraft to replace their outdated Tu-126 early warning aircraft. The platform was so well designed that it was to become a “multi-mission” capable platform. Beriev Aircraft Company had been ordered to design a maritime patrol and anti-submarine version, while some of the smaller players asked to turn it into a tanker, and Aeroflot began to express interest in using the plane as a long-range passenger aircraft.

The design went nowhere, but if you look closely at the dimensions and aerodynamics, you can see that the DNA might have found its way into China ten or so years after the Soviet napkin drawings.

Because of the fact that the Tu-156 never progressed beyond the blueprint phase, it is unlikely that there was ever a wiring schematic drawn, avionics chosen, or even engines specifically paired.

Hopping back across the Sino-Soviet split, we can see that there was clearly no external design support for any of those systems back in Shanghai. The nose, if there was any technology transfer, was clearly redesigned to accommodate the five-man flight crew. There was still a matter of the engines.

Development of the Shanghai Y-10 had begun to become so prolonged that the decision was made to power it with Pratt & Whitney JT3D-7 engines that had been purchased as spares with CAAC’s order of the Boeing 707-3J6.

If the aircraft actually flew on September 26, 1980 is a matter of debate. Many people insist that, yes, it did briefly lumber into the air. I am rather suspect of this claim. I believe that the aircraft eventually took off a few weeks later and then was pressed into touring all of the major Chinese cities.

For a flight test piece, it was low on hours before retirement in 1984- only 170 hours. Furthermore, this was done in 130 flights.

It was apparent to everyone that this aircraft was a failure. The test articles were withdrawn from service, and only one was placed in any kind of museum.

Shortly after, McDonnell Douglas was approached to launch the trunkliner program, which allowed China to construct MD-80 family aircraft to be used for civil aviation. Every single Chinese MD-80 was constructed by SAIC in what would have been the Y-10 factory.

The Y-10 might have had a short life, but it is likely that the Chinese were able to learn quite a bit about the successes and failures of building their own airliner. Let’s all hope that they have better luck with the Comac C919.

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS OF THE SHANGHAI Y-10