Poor Mr. MAX, famous for all the wrong reasons. But the dumpster fire otherwise known as 2020 gave the 737 MAX a chance to hide from the news cycle as Boeing fixed its design issues. The FAA held Boeing’s feet to the fire with the recertification, and today I have more than enough trust in the plane to fly it. I got my chance on a medium-haul flight from Miami International to New York LaGuardia earlier this summer.

After all the build-up I was expecting to be either overwhelmed or underwhelmed. But instead, I was just … whelmed. It’s a gorgeous plane, sleeker than the 737’s previous iterations. It’s quieter, has cooler onboard lighting, and plenty of under-the-hood operational benefits for the airlines. I felt very safe on the plane, and about as comfortable as one can expect to be in domestic economy. But as usual, the airline’s choice of onboard product made the biggest impact on the experience. Ultimately, the most memorable parts of the flight were the *amazing* window seat views I got over Miami and New York.

Hop onboard with me for a few thoughts on American’s 737 MAX 8, and for lots of photos and videos from the flight.

We recently flew Breeze Airways from Tampa (TPA) to Tulsa (TUL). Don’t be surprised if you’ve never heard of the airline, as it launched barely four months ago.

Two Breeze planes and Southwest’s Missouri One at TPA

Our flight was on a random Monday morning after all of the new airline buzz had died down and the inauguration fanfare had passed. No AvGeeks, no suits, no tchotchkes. Just a new airline, new crew, and lots of bargain hunters looking to excise their pent-up travel demand. We sure love an inaugural. In fact, that’s how we found ourselves in Tampa to start with. But today’s review is less flashy. Rather, we hope this is what others can expect now that some of the initial excitement and “newness” has died down.

Is it time to fly again? It’s a decision we all need to make for ourselves. But as COVID rates downtrended in some parts of the world, and with at least a chunk of the population vaccinated, this summer felt like the right moment for me. And I took advantage with a long-haul itinerary from New York to Greece. It was great being back in the sky. But very different from the way things used to be. In hindsight I guess it’s no surprise that after a cataclysmic year for air travel — and humanity in general — airports and airlines are doing things a little differently.

In case any any of you are planning your first forays back into flying, I’m sharing a few quick reactions and recommendations based on my experience. I hope they help your travels go a bit smoother!

0B5, aka Turners Falls Municipal Airport in Turners Falls, Mass. This is the airport where my AvGeek obsession first took flight, and I finally got to land and take off there this month. – Photo: Katie Bailey

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

My obsession with airplanes is directly attributable to a very loving grandmother’s attempts to settle down two very rambunctious young brothers. She’d drive us to nearby Turners Falls Municipal Airport to get ice cream and watch planes carrying parachutists from the local skydiving club while sitting on the hood of her beige 1969 VW Beetle. The high school I attended is located adjacent to the airport as well.

So, this spring, nearly 50 years later, with my relatively new pilot certificate in hand, I traveled back home and rented a Cessna 172SP from Monadnock Aviation in Keene, NH. Standard rental restrictions, such as a requirement for multiple checkout flights and having a dedicated rental insurance policy, made it easier to simply ask the folks at Monadnock to assign me a flight instructor to fly along on the trip to negate the need for the checkouts.

-

-

The detail view of our official route, which was roughly 100 nautical miles and took about 90 minutes including stopping at KORE and 0B5. Foreflight screenshot

-

-

KEEN airport in Keene, New Hampshire. Katie Bailey photo

-

-

This is a zoomed-out view for context. Foreflight screenshot. Foreflight screenshot

I’d planned out the route in advance, so I was well prepared for the flight. We’d start and end at Keene airport (KEEN), fly south over the Quabbin Reservoir in central Massachusetts, land at Orange Municipal Airport (KORE), fly northwest to my collegiate alma mater (University of Massachusetts Amherst), land at Turners Falls Municipal (0B5), and fly back to KEEN.

It was a pleasant day, with a very high overcast, light winds, and smooth air. I’d never flown over this area in a small plane, although I’d seen it from 20,000+ feet out the windows of commercial jetliners plenty of times flying home for visits. Trust me when I tell you the views from 3,500 feet are much better.

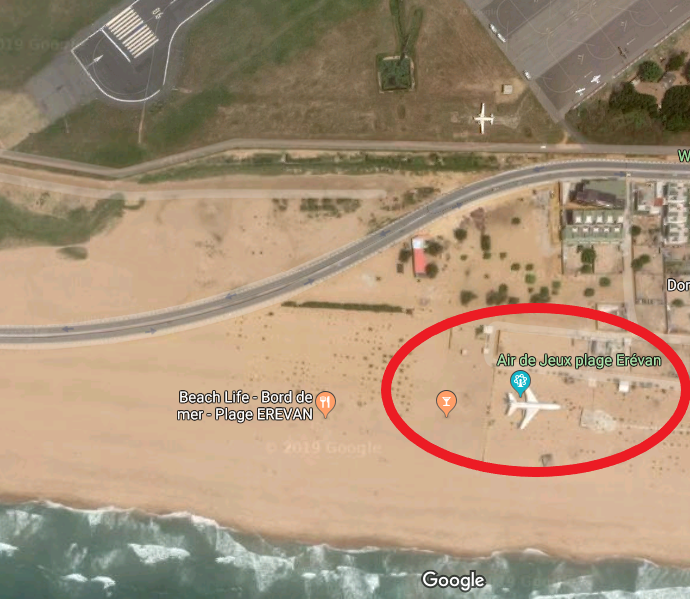

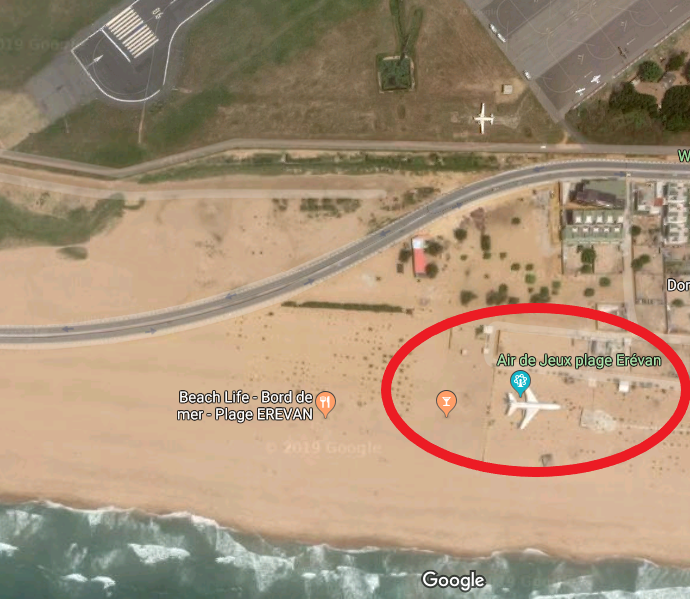

What a view! Could you imagine just seeing an L1011 on the beach? – Photo: Jerome de Vries

I was recently in Cotonou for a 24-hour layover. Cotonou is the largest city of the small west African nation of Benin, and has become a secondary hub for emerging airline RwandAir. Taking advantage of its growing network, I booked a RwandAir ticket from Dakar, Senegal to Kigali, Rwanda via Cotonou. The transit stop included accommodation provided by the airline.

What is there to do in Cotonou? A quick Google search indicated that the closest attraction to the hotel was on the beach: an ’˜amusement park’ called Air de Jeux Plage Ervan. This ‘park’ appeared to include a large-looking aircraft, so I decided to check it out. Little did I know the airframe was a historic Lockheed L1011 TriStar, full of amazing clues about its long and varied history around the world.

Mystery plane? – Image: Google Maps