Seen in 2019 – an air mail arrow outside Salt Lake City, Utah points to SLC on the San Francisco-Salt Lake route

We aren’t ready to fly. Which is a bummer because travel is a large part of our identity. What are sidelined AvGeeks to do to remain connected to our passion? We are all coping with this disaster

A 1920s advertisement bringing awareness to the TAS. – Image: Public Domain

in different ways. Looking to an aspirationally brighter future (and planning future travel) is certainly one method that holds promise. For my [formerly] frequently-traveled household we have been deep in research and planning for most of the year. As a result, our impossibly long #AvGeekToDoList has grown a great deal since our voluntary pandemic-grounding. One item of low-hanging socially-distanced fruit on our list is getting out and visiting more air mail arrows.

I have long been fascinated with the infancy of U.S. aviation. Keen AirlineReporter readers and AvHistorians alike will know that the modern aviation industry is what it is because of air mail. Indeed, all of the domestic legacies – except Delta – were formed or became successful because of income from air mail. These earliest routes were flown mostly during the day. In the evenings, mail would continue to travel, albeit via train. To further increase the speed of airmail it was determined night flying would be required. Thankfully congress stepped in to fund a vast array of large concrete arrows and beacons which formed the lighted Transcontinental Airway System (TAS.) At its peak the TAS had one concrete arrow roughly every 10 miles along the various routes. The TAS and its air mail arrows provided the infrastructure for the air mail boom which, in time, led to normalization of passenger service.

BONUS: How Delta got their non-airmail start

Join us for a discussion on how you can plan your own trip to visit these nearly forgotten 1920s-era relics of aviation’s past.

One of Alaska Airlines three newly-converted 737-700 freighters on the ramp at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport

Ever wonder about the process of loading, unloading, organizing, tracking, and planning the cargo side of a cargo flight?

Wonder no more Alaska Airlines recently invited us to watch (and then ask a metric ton of questions about) one of the airline’s new 737-700 freighters on a recent visit to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

“Alaska Air Cargo serves as a lifeline to many of the communities in Alaska where we fly,” said Jason Berry, managing director of cargo for Alaska Airlines.

“Offering reliable and consistent service is critical for us. The addition of our modern fleet paired with our proprietary navigation procedures allows us the ability to bring true scheduled service to the far north,” he said.

Alaska Airlines Ramp Service Agent (RSA) Carlos Arenas, foreground, prepares to pass a bag of mail to Lead RSA Metin Mehmedov. Both are working in the aft belly hold of the aircraft.

In preparation for the induction of Alaska’s first Boeing 737 MAX aircraft, the company’s strategy was to retire the remaining 400-series ’œclassics’ from its fleet. The five combis and single dedicated freighter were all 400-series aircraft.

According to Berry, those 400s were also getting extremely cycle-heavy, which meant they had so many takeoff/landing cycles that they were nearing the end of their useful life for Alaska Airlines.

“The decision to convert three 737-700 Next-Gen passenger aircraft to freighters meant we retain much of the same fleet commonality in terms of training and maintenance and it would give us the right-sized aircraft to still serve all the same communities we provide main deck cargo lift to today (-800s could not land at some of our current scheduled airports such as Adak, Kodiak, Petersburg, and Wrangell),” he explained.

And what’s become of those old cargo planes? Berry said all six were sold to leasing companies. “I believe you can find them for sale as we speak. I speculate that someone will eventually purchase the aircraft and convert them to full freighters.”

A Jabiru J-230D – Photo: Owen Zupp

Things weren’t looking good.

The next morning I was scheduled to depart Essendon and reenact the historic air mail flight undertaken by Maurice Guillaux in 1914. As I sat in my air-conditioned hotel room I logged onto the digital service, only to find that the weather forecast seemed endless with ’˜clouds on the ground’ at critical locations and line after line of low clouds and heavy rain. I flicked the pages on my iPad between the weather radars for Mount Gambier and Melbourne, endeavouring to get a clearer picture of the waves of water blowing in from the southwest.

Was there a possible route out of Melbourne to the west with lower hills and a higher cloud base? I entered in alternate flight plans on the iPad app and compared how much extra time such a plan would cost, and then converted that into fuel; there were viable options available. Still, the best news came from the MSL synoptic charts on the Bureau of Meteorology website. Maybe, just maybe, there will be a window of opportunity between the two deep cold fronts that threatened to ruin the centenary air mail flight.

And then I paused…

I had a world of information at my fingertips, mobile phones and mass media. 100 years ago, Guillaux had none of this and yet he set out from Melbourne bound for Sydney in his Bleriot monoplane; exposed to the elements and a simple railway line as his navigation system. On board were 1785 commemorative postcards and Australia’s first air freight ’“ orange juice and tea. His weather forecast was his line of sight through the spinning propeller. I had it easy.

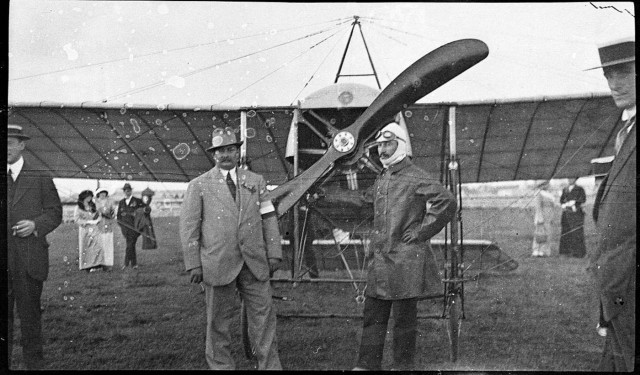

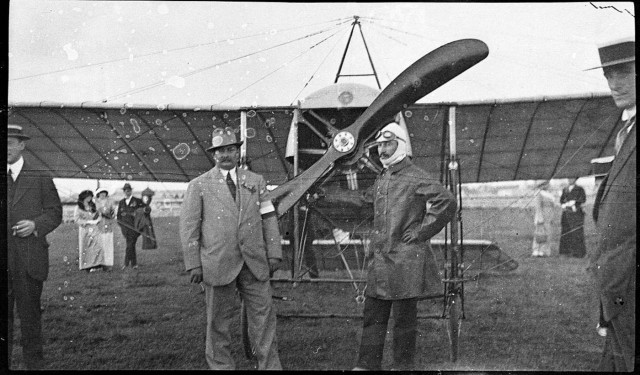

Guillaux and his Bleriot XI monoplane after the Melbourne-Sydney flight in 1914 – Photo: State Library of New South Wales | WikiCommons

It became even easier when the rain on the roof abated and breaks of blue sky appeared over Melbourne. By the time the many media commitments had been met and departure time loomed, things looked positively hopeful. Furthermore, each stage of the flight would have aircraft flying in company with my Jabiru J230D ’˜air mail’ aircraft. Veteran pilot, Aminta Hennessy, in her Cessna 182 was the support aircraft and offered an IFR alternative should the weather close in. For this stage she would be joined by a CT-4 and a Cessna 172 and all three would depart for me, offering some ’˜eyes in the sky’. As it transpired, as I climbed overhead Essendon, I could see for 100 miles and any reservations that I’d held melted away. The centenary air mail flight was underway.

Very Different Times.