An El Al 767 at Zurich airport – Photo: Aero Icarus | Wikimedia Commons

Ask any self-respecting airline geek which airline was the first to introduce commercial trans-Atlantic twin-engine services, and you’d probably get an answer like TWA, American, or maybe Air Canada. The surprising answer? Plucky little El Al, the fiercely independent but resource-challenged national airline of Israel. How did that happen?

Never shy in taking on a new challenge, El Al has built a reputation on pioneering industry breakthroughs ’“ a non-stop distance record on the JFK-TLV proving flight with a Bristol Britannia in 1957 (5,760 miles). A trans-Atlantic speed record on the 707 JFK-LHR segment in 1970 (7 hours, 57 minutes). The ultimate ’œhigh passenger density’ 747-400 operation in which a staggering 1,122 Ethiopian refugees were safely (if not so comfortably) evacuated from Addis Ababa to Tel Aviv in 1991. And a set of remarkable COVID repatriation flights in 2020.

In 1983, El Al took delivery of the first of four 767-200s from Boeing. The first two airplanes were the standard range models (4,270-mile range). The second two airframes were extended range (ER) variants, equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7R4E engines, enabling a range of 5,610 miles.

By 1984, the FAA was actively working with several operators to implement new overwater operational approvals for twin-engine operations ’“ what would become known as ETOPS- Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards. But the old rule ’“ that the flight had to stay within a 60-minute radius of a suitable landing site was still in effect.

It’s hard to wrap our heads around this today when we can fly 19 hours with up to 330 minutes ETOPS. But the notion of twin-engine oceanic operations was new stuff back then. A lot was unknown. An inflight engine shutdown would make the remaining engine work harder. Could it handle the stress? Could the one remaining generator or hydraulic pump reliably perform? And simply relying on the APU to cold-start at cruise or for the ram air turbine to properly deploy was not sufficient. Alternate airport requirements were more strict and a host of crew-training, equipage, and certification requirements made the very proposition of viable commercial ETOPS operations a daunting task.

What was clear was that the economics of twin-engine operations was quite compelling. The cost savings of operating a 767-200 with 190 passengers compared to a 370-seat 747 on a typical trans-Atlantic route was in the range of 45%. Fuel and crew costs (including the new two-person cockpit of the 767) accounted for the majority of the trip savings.

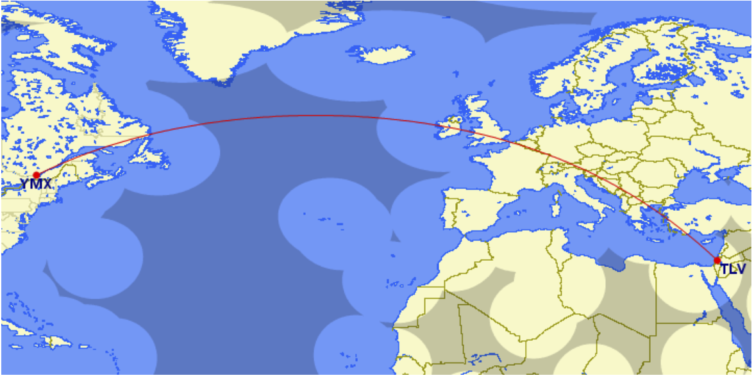

Having trialed its two ERs on shorter European runs from Tel Aviv, El Al was ready to exploit the 60-minute rule for commercial service from North America. On March 26, 1984, El Al became the first airline to offer commercial ETOPS flights, operating a 767-200ER (4X-EAC) from Montreal to Tel Aviv. The non-stop route, in compliance with the 60-minute rule, took 11 hours and 8 minutes.

El Al’s first ETOPS flight was from Tel Aviv to Montreal on March 26, 1984 – Image: Great Circle Mapper

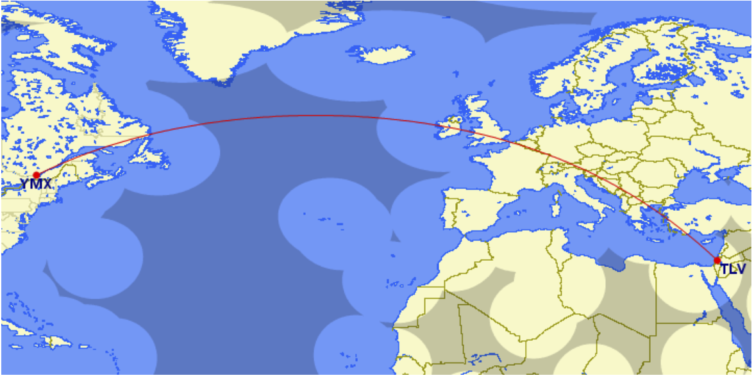

Based on the early success of the Montreal route, El Al added more ETOPS flights the next year offering 767ER service on the following routes:

- Tel Aviv ’“ Amsterdam ’“ Chicago ’“ Los Angeles (LAX)

- Tel Aviv ’“ Amsterdam ’“ Montreal

- Tel Aviv — Amsterdam ’“ New York (JFK) ’“ Miami

El Al’s early transatlantic routes were groundbreaking – Image: Great Circle Mapper

Ultimately, the airline would achieve 120-minute ETOPS approval, allowing more flexible routings on the North Atlantic runs.

El Al’s achievement was groundbreaking ’“ both technologically and psychologically. There was a lot of resistance to the idea of twin-engine oceanic flights back then ’“ from the International Federation of Airline Pilots (IFALPA) to former FAA Administrator Lynn Helms. Ultimately, technology ’“ and economics ’“ would prevail.

TWA was quick to follow El Al’s ETOPS example – Photo: Ralf Manteufel | Wikimedia Commons

El Al’s exploits were closely monitored by other airlines, eager to cash in on the favorable twin-engine economics. TWA had ten 767s on order at the time, and was working with the FAA to secure 120-minute ETOPS authority, which would allow for more direct routings from its St. Louis hub. TWA launched trans-Atlantic ETOPS flights the following year on its Boston ’“ Paris route and would go on to build a network of 767 routes from St. Louis and New York (JFK) hubs. American and Air Canada were quick to follow. The floodgates were opening.

Air Canada quickly sought ETOPS certification for its 767s as well – Photo: Michel Gilliand | Wikimedia Commons

Today, the vast majority of flights across oceans are performed by twin-engine airplanes. Few were the visionaries who could foresee that development in the early 1980s, when the very notion of twins across the ocean was controversial. But the contemporary dominance of twin-engine intercontinental flight came about only through three decades of patient, deliberate development in commercial ETOPS operations ’“ punctuated by the bold exploits of a few early movers. So, next time you board a 787 for Frankfurt or A350 to Hong Kong, you might just tip your hat to that plucky airline from Israel that started it all.

Not gonna lie – it’d be great if El Al would do a heritage livery like this – Photo: Michel Gilliand | Wikimedia Commons

About the Author: Steve Jaffe is founder and editor of airlinestoisrael.com and author of Airspace Closure and Civil Aviation — a Strategic Resource for Airline Managers. His career has spanned all facets of commercial aviation, including marketing and consulting roles at Boeing, the FAA, US Airways, and AVITAS. He remains an avid avgeek (best plane ever — the 757) and is working on indoctrinating the next generation of geeks and geekettes.

This guest story written by Gideon Afek, who is a commercial pilot and aviation historian, with a background in project management and sales; Born in South Africa, Gideon immigrated to Israel from Australia in 1985.

As soon as the new “Open Skies” agreement between Israel and the EU was announced, the three Israeli airlines came out fighting, tooth and nail. In a rare display of solidarity, both senior management and unions have closed ranks in vocal opposition, and the doomsday weapon of a strike has been quickly and easily unsheathed.

The Israeli public watch in trepidation, anticipating not only short term disruptions of travel plans, but also hear the dire predictions of the demise of Israeli civil commercial aviation as we know it, from no less than the most senior leaders of the industry.

As it stands ’“ we all should be very concerned ’“ right?

A closer inspection of the facts is revealing, and conclusions do not necessarily align to the nightmare scenario being projected to us today by the Israeli Airline Industry. The Israeli airlines have not stated clearly to what exactly in the agreements they are opposed, or, to what changes they request. In effect, they would prefer the agreement to be cancelled outright. By doing so, they request that the reality be preserved. A protected reality that is almost unknown in modern commercial air travel.

They demand that their market share be coddled and shielded by government regulation, and not by way of the merits and advantages that they offer to the travelling public. They demand that their comfort zone be preserved, allowing them to continue on as before.

The fact is that without deep and perhaps revolutionary reform within the companies, they will indeed, not be able to survive the anticipated changes brought upon by the agreement.

El Al in particular, is a deeply conservative institution. Despite being privatized from 2003, the company still functions similar to a government company of 1970’s Israel, with the associated Histadrut trade union influence and characteristics. In particular, the company suffers from a bloated and inefficient labor force and management practices, similar to airlines such as Alitalia and Iberia.

The Minister of Transport, Mr Yisrael Katz published the following statistics: “El Al employs just over 6,000 workers for a fleet of 37 aircraft, while Air Berlin has a workforce of 9,000 and a fleet of 200 aircraft.”

The CEO of the company is almost always an ex-Air Force General, such as the current CEO, Eliezer Shkedi. The only exception in recent decades was Shkedi’s predecessor, Haim Romano, and even he grew from within the security establishment. These generals have no prior commercial management experience, so it may be assumed that the airline is managed with a heavy military style and influence. No CEO has actually grown and come up through the company ranks.

These facts provide only a backdrop to the company ills. El Al today functions under an archaic strategy, one that was commonplace in commercial aviation from the 1950’s and up to the 1980’s. In those days, national carriers transported passengers to and from the mother country. The entire market in which El Al competes, comprises of flights to and from Israel alone. El Al claims a market share of roughly 25-30% of this traffic.

For El Al to earn a profit on a given flight, it needs to fill over 80% of the seats (known as the load factor). Emirates Airlines of the UAE is profitable with a load factor around 70%, in comparison.

El Al tells us that they have unique constrictions, not suffered by their competitors, such as not flying on the Sabbath and footing a bill of 50% of the incurred security costs which are approximately $100 million a year (2011 revenues were $2.4 bn) and Arab countries that they cannot fly over.

Part of the solution is to compete in a market that is hundreds if not thousands of percent larger than that of flights to and from Israel. That means moving to a “Hub” model, whereby Tel Aviv becomes a transit point for the majority of customers, instead of a final destination.

El Al will sell tickets to people who seek to travel between Europe and the Far East, for example, a flight from London to Bangkok, or Paris to Beijing. Tel Aviv will be a stopover for two or three hours. Those who wish to rest, can stay for 24 or 48 hours to get a glimpse of the cultural, spiritual and historical fruits that this country has to offer the world.

Airlines around the world use this model. El Al does not. True to at least 2011, El Al would or could not sell one ticket with such a route at a remotely competitive price.

El Al, Arkia and Israir need not view each other as bitter competitors as is the case today. They may cooperate, selling joint tickets ’“ for example, Arkia will carry a passenger from Stuttgart to Tel Aviv, from where he/she will continue with El Al to Mumbai. In this way, fleets will, to an extent be pooled, and all three companies will benefit.

We can examine airlines in the region that have adopted this Hub model and are absolutely flourishing:

- Turkish Airlines has a fleet of 212 and 284 more aircraft on order or options.

- Ethiopian Airlines has a fleet of 59 with 35 new aircraft on order or options.

- Emirates has a fleet of 186 with 263 aircraft on order or options.

- Qatar Airways has a fleet of 122 with 208 aircraft on order or options.

Granted, the Gulf carriers enjoy cheap fuel at home, but that does not deny the merit of the same Hub strategy for El Al.

The size of El Al’s current market is limited ’“ there are only a given number of people flying to and from Israel. The answer is clearly to compete for a much larger market. Such a change would not only lead to company expansion, it would also allow El AL to fly seven days a week.

Israel is well placed geographically to function as a hub for flights between Africa, Europe and Asia, despite the Arab denial of overflying rights. What many don’t seem to grasp is that airlines in the world today don’t just sell a transport solution from point A to point B.

Airlines sell a travelling experience, involving state of the art In-Flight Entertainment Systems, comfortable seats and legroom, new aircraft, internet connectivity, good food, excellent cabin service as well as safety. El Al only really excels in the last and is notorious in the former. Vast improvements in all of these can be made, the solutions exist. Should all these parameters be met, with a reasonable price, passengers will want to fly with El Al, despite the addition of some three hours to the flight due to the unfriendly Saudis.

El Al Boeing 777-200. Photo by Daniel T Jones.

Let us make a cursory examination of El Al’s fleet: There are some 37 aircraft in service with 8 orders and options published. Over half of the aircraft are 15 years old or more. The fleet includes 13 aircraft that are considered highly fuel inefficient and expensive to run by today’s standards (767-300 and 747-400) and are being replaced by all El Al’s competitors who operate such aircraft.

Should El Al decide to order the new and desperately needed 787 (Or A350) tomorrow, it will take some five years to get the aircraft, as El Al hasn’t even yet joined the back of the queue. There is no published long term fleet renewal plan, and it is unclear by what process new aircraft are ordered.

For a modern airline to succeed in trading in its marketplace, it needs a seamless IT infrastructure through which various company departments can communicate with each other. Much trade goes on between different airlines, and El Al must be able to manage its reservations system while it can interface with the systems of other airlines as well.

A very large portion of tickets are sold via the internet through all sorts of websites, such as Edreams and Skyscanner, to mention a few, and these must be exploited by the company.

Professor Judy Gittel of Brandeis University made a study of the cultural and management organization of Southwest Airlines, based in Dallas, TX. This airline has been profitable for a remarkable straight 39 years in the super-tough US Airline market. Perhaps the central pillar of their success is the organizational culture and management style that places an emphasis on excellent relations between everyone from the CEO to the last person that cleans the aircraft.

Professor Gittel identified some twelve principles that comprise the success of the airline. It is the workers who to a very large extent bring profitability and efficiency to an organization, and such is the case at Southwest.

A study of this airline can only bring benefit to an airline like El Al who is managed by a mix of military and trade union type culture.

The airline has an inflated workforce that needs to be trimmed. This is always a sensitive, if not inflammable issue. European business jet airline Netjets, who operate over 1000 aircraft needed to reduce the workforce in 2009 and set about doing so without any involuntary layoffs.

Five different options were offered to the workforce, each one involving different formulas of extended leave without pay, job sharing, university studies and several other creative solutions. The common denominator between them was a win-win situation between company and employee. Netjets succeeded in the reduction of workers, and not one was fired.

Today the three Israeli airlines fear change and they fight to preserve their meat pot as it is. It is unfortunate that the management and unions are not more imaginative and creative.

As the clich goes ’“ “change brings opportunity”, and if done correctly, Israeli civil aviation may be at the threshold of a new golden age.