A Cessna 182T looks quite similar to a C172; it has a slightly larger cowling and a more powerful engine with a three-blade constant-speed propeller. It’s rated for 230hp vs 180hp in a 172SP.

Learning opportunities are endless in aviation, and that’s one of the best parts of being a pilot.

Seemingly no sooner did I get checked out in the Diamond DA-40 than Galvin decided to sell off both of their DA-40s. I do love to fly the C172, but I also adored the DA-40. Learning to fly that aircraft, which is more complicated than a C172 with its constant-speed propeller, set me up well to transition to the Cessna 182T Skylane, which has the same style propeller, albeit a three-blade version. The T in 182T stands for turbo, which does wonderful things for the plane’s performance as well as increases pilot workload a fair bit.

The turbo essentially makes the engine think it’s at or close to sea level all the time, which means performance doesn’t taper off with altitude as with naturally-aspirated engines. The tradeoff is that not staying on top of managing the engine temperatures makes it easy to damage the engine or the turbo due to the high heat generated by the turbo and its operation.

The 182T’s engine also has 50hp more than the C172SP I’ve been flying for a couple years now, 230hp vs 180hp. FAA regulations require a high-performance logbook endorsement from a flight instructor to fly aircraft with more than 200hp, so that’s also part of the checkout training for the 182T. Galvin’s house rules require a minimum of five hours flight training time with an instructor for this plane, plus a bit of ground training to be sure the pilot knows the aircraft systems and operating procedures.

-

-

The C182T has a few more knobs and levers than the 172 to control the propeller and cowl flaps.

-

-

These are the controls for trim, cowl flaps, and fuel

Besides being a bit faster than a 172, the 182T has a considerably greater load-carrying capacity and can fly much higher – 20,000′ vs 13,500′ for the C172. The 182T is equipped with a supplemental oxygen system for flying at high altitudes.

Despite all that, the 182T handles much like a 172, if a little nose-heavy due to the larger engine. This particular model has vortex generators on the leading edges of the wings and horizontal stabilizers. This makes it surprisingly difficult to stall. Carl (my very thorough and ever-patient CFI) had me fly it during a power-on stall such that the airspeed read zero on the indicator yet we were still flying and the stall hadn’t broken yet. Super fun.

There are additional controls to manage related to managing the propeller and engine and turbine-inlet temperatures. That makes things like takeoffs, landing approaches, and pattern work quite busy for the pilot, as there’s a lot of new stuff to learn. But with practice, it all becomes manageable.

I’m currently about halfway through the checkout process. The Pacific Northwest fall weather has made flying a game of last-minute weather cancellations. Once things clear up, the next step will be a cross-country flight to an airport I’ve not yet been to, around 100 miles away from Seattle. I have several routes planned out, and the exact choice will be driven by which has the best weather along the route. Stay tuned.

0B5, aka Turners Falls Municipal Airport in Turners Falls, Mass. This is the airport where my AvGeek obsession first took flight, and I finally got to land and take off there this month. – Photo: Katie Bailey

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

My obsession with airplanes is directly attributable to a very loving grandmother’s attempts to settle down two very rambunctious young brothers. She’d drive us to nearby Turners Falls Municipal Airport to get ice cream and watch planes carrying parachutists from the local skydiving club while sitting on the hood of her beige 1969 VW Beetle. The high school I attended is located adjacent to the airport as well.

So, this spring, nearly 50 years later, with my relatively new pilot certificate in hand, I traveled back home and rented a Cessna 172SP from Monadnock Aviation in Keene, NH. Standard rental restrictions, such as a requirement for multiple checkout flights and having a dedicated rental insurance policy, made it easier to simply ask the folks at Monadnock to assign me a flight instructor to fly along on the trip to negate the need for the checkouts.

-

-

The detail view of our official route, which was roughly 100 nautical miles and took about 90 minutes including stopping at KORE and 0B5. Foreflight screenshot

-

-

KEEN airport in Keene, New Hampshire. Katie Bailey photo

-

-

This is a zoomed-out view for context. Foreflight screenshot. Foreflight screenshot

I’d planned out the route in advance, so I was well prepared for the flight. We’d start and end at Keene airport (KEEN), fly south over the Quabbin Reservoir in central Massachusetts, land at Orange Municipal Airport (KORE), fly northwest to my collegiate alma mater (University of Massachusetts Amherst), land at Turners Falls Municipal (0B5), and fly back to KEEN.

It was a pleasant day, with a very high overcast, light winds, and smooth air. I’d never flown over this area in a small plane, although I’d seen it from 20,000+ feet out the windows of commercial jetliners plenty of times flying home for visits. Trust me when I tell you the views from 3,500 feet are much better.

On final for runway 14R at BFI in a Diamond DA-40 – this wasn’t from our mountain-flying day, but it’s too pretty of a photo to leave out of the article

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

The lousy Pacific Northwest early spring weather notwithstanding, I’ve made good progress towards learning both the Garmin G1000 instrumentation and the Diamond DA-40 aircraft. We recently got a decent break in the weather that allowed a flight from Seattle across the Cascade Mountains to Ellensburg for some basic mountain flying training.

Cruising westbound at 6,500′ over Snoqualmie Pass was an amazing experience – Photo: Katie Bailey

I’ve got about 10 hours in the DA-40 now, all but one of them with Carl, my ever-patient CFI. I finally felt comfortable enough with the plane to take it out on my own last week, even though Carl had deemed me ready to do that about five flight hours previously. I just wanted a bit more time with the plane, as it’s quite a bit different than the Cessna 172, especially in that it’s a lot faster and a bit fussier when it comes to controls, and it’s got a constant-speed propeller (also sometimes referred to as a variable-pitch propeller) that needs tending to via a dedicated control lever.

Success! I finally earned my private pilot certificate!

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

After a year and a half of concerted effort, I’ve finally completed my initial training and earned my private pilot certificate in early November. It’s a great feeling!

For those who’ve been following along on my adventures at Galvin Flying, it’s been a long process of successes and setbacks, many of which were weather related because I live in the Pacific Northwest, where the local joke says that it only rains once a year it starts raining in late October and stops raining on July 5 (it always seems to rain on July 4).

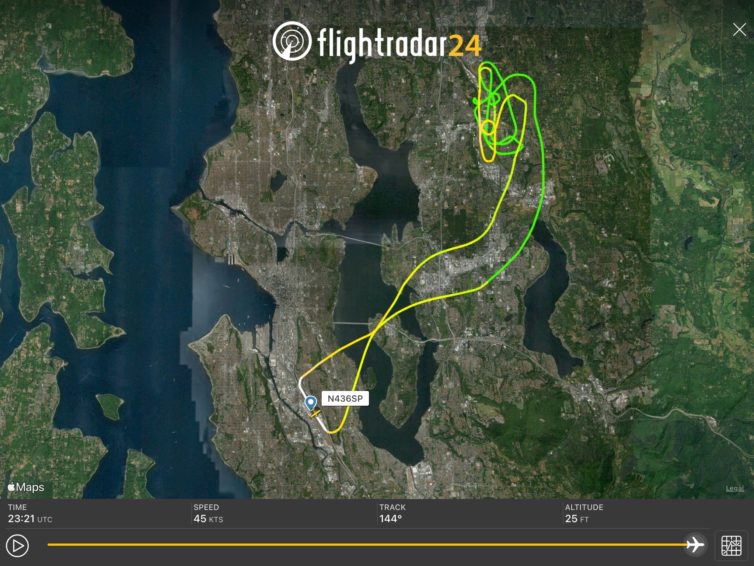

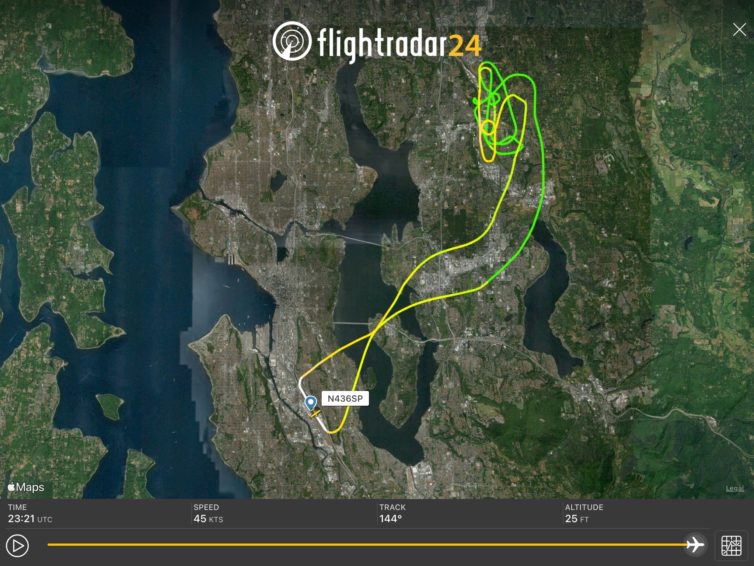

In case you ever wondered what the track of a checkride looks like, here you go. Screen capture courtesy FlightRadar24

Anyway, I did several mock checkrides in the weeks leading up to the actual FAA one, and had to complete Galvin’s end-of-course checkride before that. The end-of-course checks are designed to be more difficult than the actual checkride to ensure that pilot candidates are as prepared as possible.

The FAA examiner, also known as a designated pilot examiner or DPE, selects from a long list of information and flight maneuvers for the actual checkride known as the Airman Certification Standards. The check airman who oversees the end-of-course checks runs through the entire list to be sure you’re ready.

Likely my favorite C172 in Galvin’s fleet

This is a continuation of my multi-part series on learning to fly. You can read the whole Fly With Francis series here.

March 20 marked the one-year anniversary of my having started flight training; my first ground-school class was already more than 12 months ago.

Deciding to pursue a private pilot’s certificate has been, simultaneously, the most fiscally irresponsible thing I’ve ever done, and the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done. I’ll leave that to the reader to reconcile; I’m totally OK with the decision.

Progress has been sporadic, mostly due to a particularly bad winter with consistent low clouds that precluded flying and resulted in dozens of cancelled training flights. On the upside, now that spring is here, I’ve started to make progress again, although COVID-19 holds the potential for future disruptions. Our governor here in Washington state was kind enough to declare flight training to be among the exempted activities during the lockdown (at least for now).

Since my last post, I’ve completed both my day and night cross-country flights with my instructor, have been working a lot on navigation and flight planning, and now have returned to practicing basic maneuvers to kick off the rust from a winter’s worth of very little flying.