This is a guest blog from Vinay Bhaskara who writes for Bangalore Aviation. He recently did quite a bit of research on Delta Air Line’s historical operations at Portland and this is his blog in his own words:

Not many people are aware of it, but Delta Air Lines once had an Asian gateway at Portland International Airport (PDX). The mini-hub, which first came into fruition in the late 1980s, was actually Delta’s main Asian gateway for much of the 1990s. Unfortunately, external conditions caused the hub to be dismantled before 9/11. The following story is my attempt at piecing together the history of this unique operation, and is written in memory of all the great Delta employees who worked at Portland.

The origins of Delta’s hub at Portland can truly be traced back to the economic stories of the four Asian tigers, as well as Japan. The Asian countries of South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Sinagapore, and Japan rode industrialization and stable government policy to strong economic growth figures between 1965 and 1998 (with a few exceptions). Given the booming economies of the area, it naturally followed that traffic between the US and Asia grew exponentially during this period. And as with all exponential curves, the biggest boom happened near the end, the late 80s and 90s.

For years, services between the US and Asia had been dominated by a pair of carriers; Northwest and Pan Am. During the regulated era (pre-1978); these two carriers secured the vast majority of traffic rights across the Pacific, and almost all of the traffic rights to Asia. But following de-regulation in 1978, the US slowly began to relax regulatory controls on flying rights; and the traditional duopoly on Asian flights was broken by 1983 when American and United (the two largest US domestic carriers) received and began flights to Tokyo. United’s flight was particularly interesting.

What an amazing shot. Three different tri-holers: L1011, MD-11 and 727 all at PDX in July 1992. Photo by Delta Air Lines.

United operated flights between Chicago and Tokyo 6 times per week with a stop in Seattle-Tacoma. But one of their 7 weekly flights actually stopped in Portland; where United was far and away the dominant carrier (which dated back to de-regulation route structures). These stops in the Pacific Northwest were needed because the wide-bodied aircraft of that era couldn’t make it non-stop between the eastern half of the US and Asia. In that context, Portland made as much sense as any city as a stop-over point. While Portland was not a huge source of traffic to Japan, there were enough business links between Portland and Tokyo to warrant the one frequency.

But in 1986, United Airlines completed its purchase of Pan Am’s Asian network; still a very robust portfolio (it instantly became the most profitable portion of United’s network). With it, they acquired a host of Asian routes from their San Francisco and Los Angeles hubs, and more importantly; they acquired 747SPs. The 747SPs could fly the route from Chicago to Tokyo without a fuel stop, meaning that Portland was not needed for Pacific routes. The stop-over in Portland was eliminated, leaving city officials (relatively) desperate to maintain the nonstop link with Japan that had stimulated so much international business in the Portland area.

Enter Delta Air Lines. Around the time that United was pulling the trigger on the Portland flights, the US and Japan signed a new bilateral agreement- which allowed the US DOT to award a host of new flights between the US and Japan. Delta, who had been left out of the previous round of awards to Japan, naturally wanted to get in on the lucrative new business to Japan. But Delta was restricted by its fleet and the geographic distribution of its hubs.

The longest range aircraft in Delta’s fleet at the time was the roughly 240 seat Lockheed L-1011-500, which could not fly the 6,850 mile route between Atlanta and Tokyo nonstop. Additionally, the carrier’s other hubs in Cincinnati and Dallas Fort Worth were also too far from Japan for a route to be flown nonstop. So much like United earlier in the decade, Delta needed a stopover in the Pacific Northwest to fly to Tokyo. Seattle at this time was dominated internationally (ie: to Asia) by Northwest Airlines, who had had a large presence at the airport since before de-regulation, and as such Delta decided to fly via Portland instead.

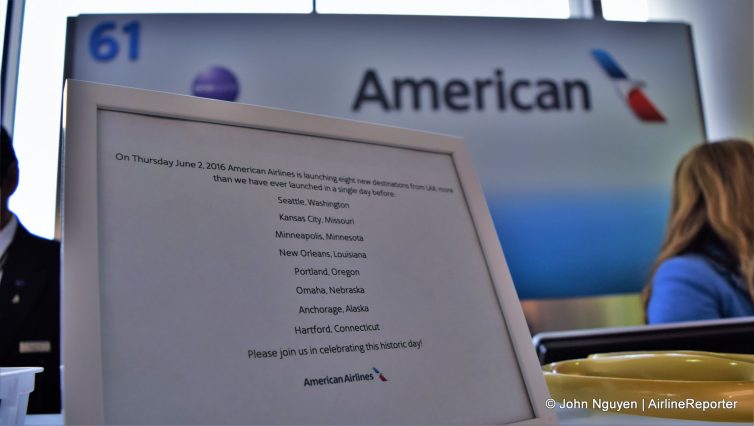

On May 13th, 1985 (before United officially ended their Portland-Tokyo segment, though the writing was on the wall), Delta officially announced that it would apply to serve Tokyo from Atlanta. Additionally, the carrier foreshadowed future flights from Portland by pointing out that Oregon’s largest city was located almost directly on the flight path from Dallas-Fort Worth and Cincinnati to Tokyo. At the time, Delta in Atlanta was the world’s single largest airline hub by flight count, with 375 per day.

On January 21st, 1986, Delta officially filed with the DOT for the rights to serve the Atlanta-Portland-Tokyo route with 5 flights per week on Lockheed L-1011-500 aircraft. The flights would depart Portland at 2:45 pm (except on Monday and Wednesday), and arrive at Tokyo-Narita at 6:05 pm the next day. The return flights would leave Tokyo at 3:00 pm (except on Tuesday and Thursday), and arrive in Portland at 6:25 am on the same day. Additionally, the carrier would add one daily flight each from Portland to Dallas-Fort Worth and Cincinnati.

The carrier explained these new flights and the new Portland operation very concisely: ’œIn addition, Delta would collect passengers and freight at those hubs and bring them to Portland, where they would connect with Delta’s flights to Tokyo.’ Even at its peak, the Portland gateway was never much more than a way for Delta to funnel passengers from its domestic hubs to Asian destinations- they never served more than a handful of non-hub cities from Portland. All of the new services began that fall.

In its comments about the Portland market to Tokyo at that time, Delta noted the strong business ties between the two cities but also touched on an interesting factor that drove tourist traffic. In the 1980s, there was a show on Japanese television called ’œFrom Oregon with Love,’ which detailed the story of an orphaned Japanese child who moves to Oregon to live with relatives. Apparently, the show was so popular with Japanese viewers that many of them new Oregon very well; and were eager to visit.

Within a year, Delta expanded the route further. In mid-December, 1987, Delta announced that it would be opening service to Seoul, South Korea from Atlanta and Portland via Tokyo. These Atlanta-Portland-Tokyo-Seoul flights (Delta 53 on Lockheed L-1011-500s) departed Atlanta at 11:51 am on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, arriving more than 29 hours later, on the next day in Seoul at 9:20 pm. The return flight (Delta 52 on the L-1011-500s) left Seoul on Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at 11:50 am, arriving in Atlanta at 2:52 pm the same day.

These new flights to ’œThe Land of the Morning Calm’ (a moniker that has since fallen out of use), were timed to coincide with the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics, which were expected to significantly increase traffic between the two nations. Korea was already the US’ 7th largest trading partner at the time, and Delta was among the last of the major US carriers to tap into those business ties. As the first single-plane service between South Korea and the Southeastern United States, Delta’s Seoul service certainly represented a strong step forward for ties between the two regions. But the 29 hour, 2-stop albatross was still a far cry from the 15 hour nonstop flights enjoyed by Atlanta and Seoul today.

Within less than a year, demand on Seoul service had surprised to such an extent, that the flights were scheduled to be de-coupled from Tokyo service, with an additional Taipei tag to boot. On March 23rd, 1988, Delta announced that it had filed with the DOT for the rights to serve Portland-Seoul-Taipei with daily flights. The Portland-Seoul leg, which was previously operated 3 times per week as part of 6 weekly Portland-Tokyo services, departed Portland at 1:00 pm, arriving in Seoul at 5:55 pm the next day. The extension to Taipei arrived at 8:35 pm on the day of arrival.

Meanwhile, the Tokyo service was also being re-timed. Business travelers had apparently complained that the 6:00 am arrival time was too early; because it was before the business day started and before most hotels allowed check in for that evening. Despite that, Delta CEO Ron Allen stated that the route was profitable, in spite of roughly 60% seat-loads. Service was expanded to daily, and the new schedule called for flights to depart Portland at 1:15 pm, arriving at Tokyo-Narita at 4:30 pm the next day. The return flight to Portland arrived at 10:25 pm.

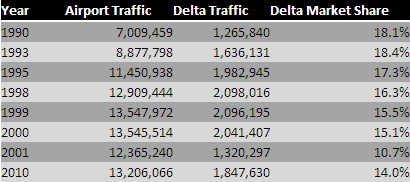

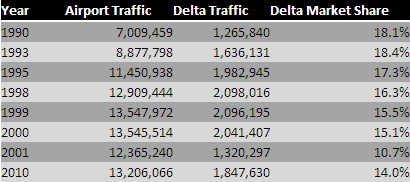

A table of historical traffic data for PDX.

The re-timing of Tokyo flights and new flights to Seoul marked a paradigm shift in the function of the Portland operation. Initially designed as an ’œend’ to means of connecting Atlanta to Asia one-stop, the success of the flights and the merger with Western (which added Salt Lake City and Los Angeles to the growing list of Delta destinations at Portland) convinced Delta to make Portland a true ’œhub’ (though on an extremely narrowed scale). Both Asian flights now departed and arrived soon after one another, allowing for efficient connections to and from Delta’s major domestic hubs.

Perhaps recognizing this new normal, Delta decided to expand upon and improve its Portland facilities as well. Delta, which had previously operated four gates (46, 47, 48, and 49 on Concourse K), expanded with 3 new wide-body gates, a new premium Crown Club, an expanded flight lounge, and a temporary10,000 square foot clearance and departure area (for US Customs and baggage handling), located beneath Delta’s departure lounge (not to be confused with premium lounge) and capable of serving 600 passengers per hour. By Christmas of 1988 (when the whole project was scheduled to be completed), the 10,000 square feet of temporary added space would be expanded to a 35,000 square foot, permanent installation.

The new facilities supported Delta’s expansion, and it continued to grow facilities in 1989 with the construction of a new 7,000 square foot first class lounge, as well as two new gates. One of the biggest selling points of Portland service was the ease with which Customs was cleared: with times averaging about 25 minutes. Korean customers in particular raved about the ’œexcellent’ treatment they received from Delta employees in Portland, many of whom spoke fluent Korean. The ease of travel attracted many business travelers, and was even cited by Portland mayor Bud Clark (and Delta’s Portland employees) to have been a factor in drawing a $30 million expansion by Fujitsu in the US to Portland.

While most of the country underwent a recession from1989-1991, Portland’s operation bucked the trend. Flight levels were maintained throughout, and in 1989 the Portland-Seoul-Taipei flight was extended to Bangkok as well. The aircraft operating this flight was certainly amongst the most heavily utilized in Delta’s fleet, as the 1:10 pm departure did not arrive in Bangkok until 12:30 am, two days later! Furthermore, the carrier chose to expand facilities even further, with a new $6.4 million, 85,000 square foot facility being announced in November of 1990.

The new facility would be jointly used by Delta’s cargo and cabin service teams. Additionally, Delta announced new service to Nagoya, Japan, beginning February 7th, 1991. The new flights departed Portland at 1:00 pm, arriving in Nagoya at 4:40 pm the next day. After less than a 2 hour layover, the return flight would depart Nagoya at 6:35 pm, arriving in Portland at 10:05 am the same day. As with all of Portland’s flights to the Pacific Rim, the new flights were operated with Lockheed L-1011-500s, though Delta did indicate in its press release that it planned to introduce MD-11 service soon after.

During this period, Delta’s operations and Portland’s airport expanded in tandem. By 1991, Delta had added domestic service to Anchorage, San Francisco, Vancouver, and Seattle. And the airport, after seeing traffic decrease slightly at points in 1989, increased traffic continually throughout the downturn, hitting 6.378 million passengers in 1990. And cargo growth was even more spectacular, more than doubling between 1982 and 1991. Delta in particular drove the growth, though 16 cargo carriers had service to Portland by 1991, many of them serving the Far East. Delta also touted its new McDonnell Douglas MD-11 aircraft, which upon entering service, would significantly increase Delta’s cargo carrying capacity in Portland.

By 1994, Delta had re-gained enough confidence in the sluggish economy (which had limited growth between 1991 and 1993) to announce a major new expansion of facilities. Delta’s ticket counter was expanded from 11 positions to 17, a gate was added, with 4 being upgraded to make 10 total gates; 7 capable of handling widebodies. MD-11 service had entirely replaced the L-1011s, and Delta had even de-coupled the Taipei-Bangkok leg from Seoul twice weekly (Taipei was served via Seoul the rest of the week, Bangkok not at all), and introduced new nonstop service to New York JFK, the only scheduled trans-continental flight (to the Northeast) at that time in Portland. Portland had even grown to play a larger role in Delta’s overall operations. More than 700 flight attendants were based at the airports, as were 120+ pilots. And as the MD-11’s most important ’œhub,’ the tri-jets had their maintenance base in Portland as well.

While 1994 was not technically the peak of Delta’s operations in Portland, it did represent the height of Delta’s operation for a while. As the US economy dove headlong into the Tech boom of the mid to late 90s, Delta began to shift its focus to domestic and European expansions. Incoming MD-11s were quickly shifted to Trans-Atlantic flying and service to Taipei and Bangkok from Portland ended in 1995, and to Anchorage in late 1994 (nonstop service had ended in 1992). But despite these cuts, Delta maintained a plateau in Portland, adding passengers, increasing its market-share, and up-gauging to larger equipment on domestic routes. The US and world economies continued to ride the world-wide web to new growth, and Delta’s operations in Portland remained solidly profitable.

And then came 1998. As the US economic boom was pushing towards its absolute peak, Delta embarked on a rapid expansion from Portland. New domestic nonstop service was added to Boston and Las Vegas (double daily). New service was launched to Fukuoka (Japan’s fourth largest city), and that summer, even loaded service to Osaka’s new Kansai International Airport into the timetable. All told, Delta operated about 30 daily flights at Portland that summer, serving 4 Asian destinations non-stop. 1998 represented Delta’s operational peak at the airport, though 1997 saw more passengers carried.

And then, just as quickly as the build-up began, the wheels began to fall of entirely. Since late 1997, much of Eastern Asia had been gripped by financial crisis related to currency manipulation. But thanks to strong US demand, passenger traffic to Asia had not yet completely fallen off. But by late 1998, Japan had slipped into recession, South Korea was in the dregs of its deepest economic downturn ever, and the economies of the region were generally in malaise. Thus, early in 1999, service was unceremoniously dropped to Seoul and Fukuoka, though the carrier did term them suspensions. The US economy (surprisingly) maintained its economic strength, keeping the decline in passenger traffic carried by Delta in Portland small, at 1.4% (though nonstop service to Boston was cut).

And as the US tech bubble started to cool, the Portland hub breathed its last, gasping breaths. In September of 2000, Delta announced that it would be ending Portland’s role as an Asian gateway, effective April 1st, 2001. Service to Tokyo and Nagoya, which had been operating continuously since 1986 and 1991 respectively, was ended, as was domestic service to Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco and Vancouver. 330 positions were eliminated in April, and in the wake of September 11th, the pilot and flight attendant bases were disbanded. By the end of 2001, Delta operated just 11 daily flights to 4 destinations (Atlanta, Cincinnati, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Salt Lake City). Annual passenger traffic for Delta decreased 34.1% year over year; it would never again cross the 2 million mark.

Delta Air Lines MD-11 (N803DE) on the tarmac at Portland in July 1992. Photo from Delta Air Lines.

Delta’s Asian gateway at Portland is unique in the annals of US airline history as an international connection-driven operation that functioned well, in spite of the lack of a true domestic hub. Many have theorized that Delta lacked sufficient feed to truly allow the Portland hub to survive, claiming that to be its fatal flaw. But Portland’s operation was as much a victim of economic hardship (the Asian financial crisis), and advancements in aircraft technology to boot. The new generation of Boeing 777 and Airbus A340 aircraft was soon able to fly non-stop flights between the Eastern US and Asia, reducing the need for a scissors hub on the west coast. Delta in particular, was quick to introduce nonstop flights from Atlanta and New York JFK to Tokyo.

Furthermore, Delta never really was a true domestic competitor at Portland. Even at its peak, the carrier lagged behind United and the Horizon-Alaska duo in market-share; limiting the potential of domestic expansion for Delta. Perhaps if it had used the 767-300ERs it does in Seattle today, with additional feed through its code-share with Alaska Airlines (and Horizon Air)?

For Portland, the loss of Delta’s ’œhub’ was not the end of its world. Passenger traffic has rebounded past its late 90s peak, and the facilities built by Delta still serve the airport well today. Portland has seen service during the 2000s from Lufthansa to Frankfurt, but it was previously little known (in Portland at least) Northwest Airlines that drove the true expansion. With nonstop service to Amsterdam and Tokyo added in the mid-2000s, Northwest quickly became the airports second most important tenant. And perhaps in the future, there may be another US-Asia hub at PDX.

Post Script: In 2009, Northwest and Delta consummated their merger, meaning that Delta once again operated long haul international flights from Portland International Airport (to Amsterdam and Tokyo-Narita). In the summer of 2011, Delta operated roughly 15 daily flights from Portland, serving 6 different destinations. In July of 2011, the carrier held a 13.3% market-share at the airport (excluding operations by SkyWest to Salt Lake City).

SeaPort Air Pilatus PC-12 (N58VS) parked at Portland before our flight back to Seattle.

You might be an aviation geek if you take a flight, wait around for five minutes, then get back on the plane to fly home. I love doing that stuff and I recently got to fly SeaPort Air from Seattle to Portland to check out their product (disclaimer: I did not have to pay for my flight).

SeaPort Air is one interesting airline. Service started in June of 2008 flying between Seattle and Portland. However they not only fly to additional destinations in Oregon, they also fly to destinations in Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri and Tennessee. Say what? Do not worry, I will explore the airline’s interesting history in another blog. On this one I want to take a look at their flight from Seattle to Portland.

Not a shabby view. Nice thing about a small plane is you can take photos out of your neighbor's window.

Unlike most other flights out of Seattle, that leave from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA), SeaPort flies out of King County International Airport (aka Boeing Field – BFI), which is located just north of SEA. The big benefit of operating out of BFI is no TSA. That means, no privacy invading body scanners, no putting your toiletries into a ziploc bag and no waiting in long lines. SeaPort has no problem advertising the lack of TSA. On their website they state, “No lines. No rubber gloves. No need to take your shoes off. Simply arrive 15 minutes before your flight, board and go.” What a simple concept. SeaPort shares a common ticket and boarding area with Kenmore Express, the only two scheduled airlines that currently operate out of BFI.

This aircraft was in executive configuration. Yes, that is suede on the walls and ceiling -- classy.

SeaPort is geared towards the business traveler. They fly the Pilatus PC-12 which they have set up to hold 6-9 passengers. My flight was in an executive configuration of six passengers and I got to sit backwards flying south (photo of commuter configuration). With the pressurized cabin, turboprop engine and executive layout, the flight really felt VIP. During flight, the Pilatus felt much larger than other aircraft of the same size.

My big regret was not sitting on the left side of the plane on the flight down to Portland. Even though it was the middle of November, the sky was clear and there was plenty of great mountain eye-candy to be seen. Luckily for me, the passenger sitting next to me didn’t mine me taking a few shots out his window (he was sleeping). When coming back to BFI I wanted to sit on the right side to catch the views I missed on the way down. However Christian, one of the pilots, suggested I sit on the left side. He explained we would be doing a fly-by of downtown Seattle on a northern approach to BFI and it would be worth it. I took his advise and I am glad I did. Unfortunately it was night time by the time we reached the city, which provided an amazing few, but taking photos was difficult (photo).

Speaking of pilots, you will find two of them upfront. Airlines are able to fly with only one pilot on the Pilatus PC-12, but SeaPort has decided to fly with two. This is an unusual business decision, since not only does the second pilot cost more money, they also take up a seat that could be used for revenue. Although most passengers prefer having two pilots, I prefer only having one, since that gives me a chance to sit in the empty co-pilot’s seat.

Even though there is no direct BFI-PDX competition, both Horizon (with their their Q400’s or CRJ700’s) and United Express (with their E120s) fly on the SEA-PDX route. Flying on SeaPort Air via BFI versus others airlines at SEA definitely has some benefits. Passengers get free parking both at BFI and SeaPort’s terminal at PDX and of course you don’t have to deal with TSA at either. Even though SeaPort’s ticket prices might be a bit higher, when you factor in free parking and no bag charge, the overall cost becomes very competitive.

Time, especially with business travelers, can be worth much more than money. When I landed back at BFI, from the time the plane was stopped, to me pulling out of the parking lot in my car it was about three minutes (yes I was timing it). Try doing that at SEA.